Potassium sodium tartrate made its mark centuries ago in the hands of scientists who aimed to unravel the mysteries behind electric currents and chemical changes. The compound’s early roots trace back to French chemist Pierre Seignette, whose work in the 17th century propelled Rochelle salt — another name for potassium sodium tartrate — into science’s spotlight. The salt didn’t stay on the shelf as a chemical oddity. By the 1800s, it became a workhorse in food preservation, household medicine, and even glass production. Its fame peaked again in the early 20th century thanks to its unique ability to convert mechanical pressure into electrical signals, giving rise to piezoelectric devices such as gramophone pickups and ultrasonic transducers. The story of potassium sodium tartrate tells more than a tale of chemistry textbooks; it captures the way simple discoveries often snowball into world-changing technology.

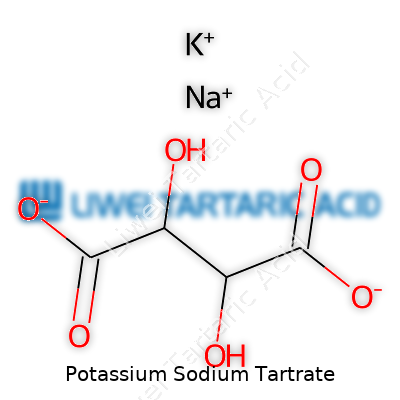

Potassium sodium tartrate comes as colorless, transparent crystals that dissolve readily in water, leaving behind a sweet aftertaste. Its formula, KNaC4H4O6·4H2O, identifies a compound with two alkali metals and a rich legacy. Most folks know it as Rochelle salt, though other names pop up depending on country and industry. Its uses branch out wildly, from old-school baking powders to major analytical chemistry labs. Even if it doesn’t get star billing in popular culture, potassium sodium tartrate plays steady roles in still-necessary fields like metal finishing, chemical analysis, and the development of newer, greener electronics.

Solid at room temperature, potassium sodium tartrate feels soft and dissolves with little effort, blending easily into water to yield a mildly alkaline solution. The crystals appear clear and striated under a microscope, reflecting light in interesting geometric patterns. The salt starts to lose its water content around 55°C and melts with decomposition if heated beyond 80°C. As a piezoelectric material, compressing or flexing a crystal generates a voltage across its surface — a property that once helped run the first loudspeakers and still powers certain sensors today. Chemically, it resists most weak acids and bases, but strong acids can break the molecule into tartrate ions, which in turn help bind and transport metal ions in solution.

Manufacturers selling potassium sodium tartrate usually supply it in granular or crystalline forms, packed in airtight bags or moisture-resistant drums. The product often carries labels showing a minimum assay of 99.5% purity, along with heavy metal content that falls well below pharmacopoeia thresholds. Spec sheets cite attributes like solubility (20g/100 mL at 20°C), specific gravity (about 1.79), and water of crystallization (4 molecules per unit). Each container requires a clear hazard label if the salt’s destined for laboratory use, and the safety data sheet lists CAS number 6381-59-5 for clarity across borders and shipment types.

The standard process starts with tartaric acid, harvested from winemaking byproducts or synthesized straight from sugar. By neutralizing this acid with a blend of potassium carbonate and sodium carbonate, chemists create a solution that, upon cooling, deposits well-formed potassium sodium tartrate crystals. It takes patience to coax big, regular crystals out of the batch, so controlled cooling and occasional seeding help. Once formed, the crystals are washed, dried, and sorted before packing, with each step monitored for unwanted residue. This classic route still dominates because it’s simple, scalable, and delivers the purity that both food manufacturers and electronics engineers demand.

Potassium sodium tartrate likes to play matchmaker in chemical reactions, coordinating with calcium, copper, and other metals to form stable tartrate complexes. In Benedict’s and Fehling’s solutions, it helps reduce simple sugars, making it essential for diagnosing diabetes in the past and for lab analysis today. Heating in the presence of acid or strong oxidizer breaks down the molecule, releasing carbon dioxide and freeing carbonate or formate ions. Tinkering with the tartrate backbone cracks open research into newer piezoelectric materials, where even small substitutions can boost or dampen electrical output. Modern labs explore grafting different metal ions onto the tartrate molecules or blending the salt into composites that broaden its utility in electronics, optics, and even drug delivery.

Names vary by industry and country, but a few always pop up: Rochelle salt, Seignette’s salt, Potassium sodium L-(+)-tartrate tetrahydrate, E337 (as a food additive), and CAS 6381-59-5 keep everyone on the same page. German companies might market it as “Rochellesalz,” while English-speaking chemists lean on the more formal chemical names. Each label signals the same core function, yet inspires different applications, enough to create a tangle for anyone flipping through international procurement catalogs.

Working with potassium sodium tartrate rarely causes headaches for those respecting basic safety routines. The crystals should never go near open flames, not just for fire risk but because breakdown products could irritate lungs and eyes. Gloves and goggles are standard for lab workers, and anyone packaging bulk product in a factory has to stick with dust masks until packing finishes. Guidelines issued by OSHA, the European Chemicals Agency, and major pharmacopoeias all agree: keep exposure low, never eat or inhale the material, and mop up any spills with dry sweeping. Training stays essential wherever large batches are processed, and always read the SDS sheet every time a fresh shipment lands.

Potassium sodium tartrate’s presence in industry covers surprising ground. Analytical chemists value it as a stabilizer and reducer in reagents, especially in the detection of aldehydes and sugars. Food scientists use its ability to adjust taste and structure in baking powder and candy making, although tougher food safety laws limit this to destinations where it shows a history of safe use. Tanners, textile makers, and metal finishers keep it around for treating water and stabilizing dye baths. Maybe the most curious chapter comes from electronics. The days of haul-sized Rochelle salt crystals powering microphones might have faded, but you’ll still find small slivers inside specialized military, medical, and research devices. Creative uses keep emerging, especially as folks hunt for lead-free piezoelectric materials that match the old strengths but avoid modern toxicity worries.

University labs and corporate research groups constantly test what potassium sodium tartrate can do with a little tweaking. In catalysis, researchers follow how the molecule grabs and releases different metals, hoping to design smarter, cheaper industrial catalysts. Material scientists push past classic uses, exploring how tartrate-based composites interact with electricity, sound, and light. The hunt goes on for even bolder applications — think bioelectronics, safer food chemistry, or reusable sensors for environmental monitoring. AI-driven simulation speeds discovery, but direct experiments still matter most in sorting solid leads from chemical dead-ends.

Study after study confirms potassium sodium tartrate’s relatively low toxicity in small doses, which fits with its centuries of use in foods and laxatives. Even so, taking too much at once brings cramping, nausea, vomiting, or worse, so regulators control food-additive levels tightly. It slides through the digestive system mostly unchanged if dissolved in water, but heating it with strong acid or mixing with other chemicals can yield products that irritate the gut, kidneys, or nervous system. Recent animal tests confirm that chronic exposure at high levels affects metabolism, but doses used in industry or food rarely come close. Safety reviews from EFSA, FDA, and JECFA still shape official guidelines, balancing legacy use with modern toxicological tools.

The outlook for potassium sodium tartrate hinges on how the world addresses technology, sustainability, and health. Engineers keep searching for cleaner, stronger piezoelectric replacements, but the salt’s well-understood chemistry means it won’t disappear soon. Energy scavenging from environmental movement, biomedical sensors, and low-toxicity food processing all push for tweaks that make the old salt fit contemporary needs. If more regions greenlight its food use or electronics applications, demand could climb. Scrutiny over heavy metals and personal safety might steer companies to invest in even purer grades or cleverer composites. Young chemists might rediscover its potential all over again, tying classic knowledge to the problems and markets left unsolved.

Most people hear “Potassium Sodium Tartrate” and feel a classroom memory stirring, usually of a cluttered lab bench and the smell of something faintly sweet. Also known as Rochelle salt, this compound isn’t just for textbooks. It steps right into real life, showing up everywhere from old school science experiments to making baked goods stand tall. Having worked in kitchens and science labs both, I’ve seen its practical side up close—useful, dependable, and a bit underrated.

For those who remember the classic “silver mirror” test, Potassium Sodium Tartrate plays a supporting role. In that context, it keeps metals dissolved in water. This quality helps make test results turn out clear and accurate—crucial for chemists who rely on precision. It doesn’t just show up once and vanish, either. It appears in lessons meant to give students the confidence to understand and trust analytical chemistry. A little bit of it can teach big ideas about how minerals react, dissolve, and transform.

Potassium Sodium Tartrate doesn’t only matter in the lab. Bakers know it under a different name: cream of tartar. Stir this into egg whites, and suddenly meringues keep their shape. Add it to sugar syrups, and crystals won’t form, keeping candies smooth. I’ve found the difference unmistakable when whipping up a batch of cookies or candy. Using this simple powder can keep a whole recipe from falling apart—literally. Without it, many desserts would collapse or refuse to rise. Food safety protocols treat every ingredient like an ally or an enemy, and Potassium Sodium Tartrate sits firmly in the “ally” camp.

Factories also depend on Potassium Sodium Tartrate. Electronics need metals carefully coated in thin layers, and this salt steps in here, too. It carries metal ions and makes sure the final finish looks even and smooth. From circuit boards to jewelry, industry relies on it to bridge the gap between raw material and polished product. I have seen production lines where a missing batch can throw off an entire day’s output. Quality checks often involve this salt, because a tiny error means an end product that fails the customer.

Despite its broad range of uses, storage and handling require real attention. Since it works both in food and labs, companies watch for cross-contamination risks. Bad labeling or poor training can result in the wrong salt ending up in the wrong place. My experience in food safety shows that careful tracking of every container and clear training for staff can head off these problems. In industry, collection and disposal need strict rules so this compound doesn’t end up in wastewater. Most factories now use closed systems and regular audits to catch leaks or mix-ups early.

Science doesn’t stand still, and neither does the use of Potassium Sodium Tartrate. Newer kitchen gadgets sometimes claim they can replicate its effects with less fuss, but the classics hold strong because people know and trust them. Meanwhile, researchers and manufacturers push for greener ways to recover salts and reduce waste, investing in smarter recycling systems. Those actions go beyond saving money—they build trust among consumers and workers alike. In labs, kitchens, and assembly lines, this simple compound finds a way to make every process stick together just a bit better.

Potassium sodium tartrate doesn’t land in most kitchen conversations, yet it’s been blended into foods for decades. Its other name, Rochelle salt, might show up on ingredient lists in items like baking powder or certain candies. The idea of adding salts with names you’d recognize from chemistry class can make anyone pause, but this compound keeps a surprisingly steady record when it comes to safety in food.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration classifies potassium sodium tartrate as “Generally Recognized As Safe” (GRAS) when used under standard food processing conditions. Across Europe, the European Food Safety Authority has a similar approach, pointing out that it doesn’t pose trouble when kept in reasonable doses. It finds its way into kitchens more for function than flavor, often stabilizing eggs in meringues or jellies. Many bakers trust it to keep their creations steady and fluffy.

For the average person, potassium sodium tartrate shows up in such trace amounts that it wouldn’t tip the scales on anyone’s health chart. Over time, science hasn’t found convincing links between this ingredient and health issues in healthy adults. The salt doesn’t build up in the body, either. The kidneys flush it out like many common minerals we eat each day.

People with kidney problems or very unusual mineral imbalances need to watch how much potassium or sodium they consume from all sources. In the real world, compared to chunky amounts of added table salt or processed foods, the tartrate component barely registers. Big science panels have repeatedly sorted through data and end up at the same conclusion: no real threat for most folks at home or in restaurants.

With so many ingredients blending into packaged foods, clear labeling stays vital. People deserve to know exactly what sits in their snacks. Anyone with allergies or rare metabolic problems, especially those involving kidneys or heart, may want to talk to their doctor about ingredients like potassium sodium tartrate, since both potassium and sodium play important roles in how bodies balance fluids and nerves. Still, the salt doesn’t act like table salt—a sprinkle in a cake doesn’t raise blood pressure or pose the same risks as overdoing salty chips every day.

If someone chooses to skip foods with additives like potassium sodium tartrate, recipes don’t get ruined. Egg whites whip up just fine with a little vinegar or lemon juice. Chefs often lean toward these old-fashioned hacks for home cooking. In commercial kitchens and mass production, though, the precision and predictability of potassium sodium tartrate help chefs pump out perfect batches.

Looking at the science, eating foods made with this ingredient sits as safe for most people. Those still worried can stick to whole foods or cook from scratch more often. That cuts out nearly all additives, not just this one. As ingredient lists get shorter and clearer, everyone stands to benefit—especially the picky and the careful.

Most eaters won’t notice potassium sodium tartrate in their diet, and doctors rarely mention it in checkups. Trust between eaters, bakers, and food companies matters, and solid oversight from regulators helps those relationships work. If food labels keep things honest and folks use basic cooking wisdom, there’s little reason for alarm.

Potassium sodium tartrate, known by folks in science classrooms as Rochelle salt, does a lot more than sound fancy. Schools and research labs use it to grow crystals and show how piezoelectricity works—the property where squeezing a crystal creates an electric current. Having seen these experiments up close, I can say it’s not just textbook fluff. Watching a slab of this compound spark a buzzer with a simple press can make science feel alive, and that kind of engagement encourages young people to stick with STEM fields. In the long run, real-world demos like these help form a foundation for bigger breakthroughs.

Walk into any commercial bakery, and there’s a good chance potassium sodium tartrate has played its part. It acts as a stabilizer for egg whites, giving meringues or angel food cakes their signature light and airy feel. Without it, those peaks might slump, leaving desserts flat and cooks frustrated. It also helps with sugar crystallization in candies, and offers a solution for confections that rely on smoothness and texture. I’ve had my share of kitchen failures, and a little scientific know-how goes a long way. The food industry leans on this knowledge daily—there’s a direct link between these chemical tweaks and the quality on grocery shelves.

Dip a piece of metal in a bath and coat it with nickel or silver—electroplating is at work. Potassium sodium tartrate keeps metal ions suspended and helps them stick to surfaces more evenly. A poorly prepared bath can mean patchy or bubbled coatings, which shortens the life of everyday objects. From cutlery to electronics, everything benefits. Reliable plating cuts down on waste and saves cost—businesses always look for ways to run tighter ops, but safe chemistry makes it possible. It’s not just about shiny finishes; it’s about building things that last.

Medicine belongs to a strict world where consistency matters. Many laxative formulas use potassium sodium tartrate because it triggers water to move into the intestines, helping people manage irregularity. When used responsibly, it offers relief without resorting to harsher solutions. Getting doses right protects patient health, and the stakes climb further up when you remember that many folks can’t tolerate stronger laxatives. Every good pharmacist knows the value of compounds that do their job with fewer side effects.

Industrial cleaning crews face tough jobs—grease, tarnish, and buildup don’t respond well to elbow grease alone. Potassium sodium tartrate helps mix cleaning formulas that loosen deposits from metals without causing too much wear. In my own experience, a good polish doesn’t just make things look clean; it keeps restaurants, hospitals, and even public transit running safely and smoothly. Choosing the right cleaning agents also reduces toxic runoff and supports safer workplaces.

Every application above stands as proof that simple compounds can do complex jobs. Still, we don’t always need to reach for chemicals when a more natural process can do the trick. Constant review of these uses, plus honest reporting about workplace exposures, keeps both factory workers and end users safe. Advocating for research into alternatives that are less hazardous and more sustainable makes sense. Responsible use, transparency, and looking for safer upgrades—all these steps help keep industry running and people protected.

Potassium sodium tartrate, sometimes called Rochelle salt, pops up in everything from laboratories to bakeries. You’ll spot it on food labels as E337. Manufacturers use it as an emulsifier or acidity regulator in things like caramel or as a leavening agent in baking powder. Over the years, anyone with a curiosity about odd ingredients in recipes or chemistry sets has probably stumbled upon it.

People hear the word "salt" and immediately start thinking about sodium, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular worries. In potassium sodium tartrate, both sodium and potassium appear, but in very different proportions compared to table salt. Small amounts pass through healthy kidneys and leave with little fuss. Healthy bodies balance these minerals quickly.

Food-grade potassium sodium tartrate doesn’t have a notorious history of toxicity when used as directed. Still, some people feel uneasy about any additive. That’s understandable—a decade of headlines urging caution about food ingredients will do that. Potassium sodium tartrate remains approved in Europe and North America after safety authorities reviewed studies and set use limits.

Large doses, beyond what you’d find in food, can run into trouble. Back in the 19th and early 20th centuries, doctors used it as a laxative because it draws water into the intestines. Take too much, and it leads to diarrhea, cramps, nausea, and dehydration. No one grabs handfuls of baking powder for lunch, but it’s always possible a child or someone confused about doses might swallow more than intended. In those cases, quick medical help stops serious harm.

A more subtle risk comes for people with existing kidney or heart problems. Extra sodium, no matter how it’s packaged, adds an extra burden for kidneys that don’t filter efficiently. Potassium sounds healthy, but too much can also disrupt the rhythm of the heart, especially for anyone with compromised health or those taking medications that interfere with mineral balance. That’s a small group, but it does exist.

Industrial potassium sodium tartrate sometimes sits next to cleaning chemicals or solvents. Accidentally using lab-grade or industrial samples in food brings trace impurities no food authority would accept. That’s why labels, sourcing, and storage always deserve a double check, both at home and in restaurants.

Shelf life rarely causes problems. Rochelle salt lasts well unless it draws in humidity and clumps. Toss any lumpy or off-smelling powders.

Checking labels carries real weight. Anyone with kidney disorders, heart failure, or who takes diuretics or ACE inhibitors should ask a pharmacist or doctor before adding extra potassium sodium tartrate to the diet. Parents need to store baking products safely, just as with other kitchen chemicals. If anyone swallows more than a teaspoon on purpose or by accident, it’s smart to get medical advice without delay.

For the average healthy person eating typical amounts of processed foods or baked goods, potassium sodium tartrate brings little risk. Concerns ramp up only with high doses, certain health conditions, or if non-food grade products make it into the kitchen. It’s another reminder that most issues with food additives result from forgetting where they came from, mixing up labels, or ignoring guidance built on decades of experience and study.

Seeing a bag of potassium sodium tartrate on the shelf probably doesn’t spark much excitement for most people. Those who spend time in labs or food production know it for its role as an ingredient, reagent, or cleaning agent. In my own lab days, I remember how a seemingly simple compound could become a big problem if ignored or mishandled. This stuff deserves thoughtful care as it spends its life both helping and, sometimes, causing trouble if overlooked.

Potassium sodium tartrate lasts well when it sits in sealed containers made from tightly lidded plastic or glass. Dampness shortens its shelf life, so stashing it away from sinks or humid basements gives the best results. I’ve watched a jar go lumpy within days because a careless team left the lid off. Once moisture gets inside, the crystals clump and the compound starts losing usefulness fast.

Sunlight and heat matter, too. In a sunlit storeroom, temperatures change fast and the stuff can start to break down. I once saw it lose clarity, so the crystals went from clear to clouded overnight after the jar spent time by a window. So, a cool, steady space protects the investment.

Labels and separation help avoid confusion. Similar-looking substances, especially white powders, easily swap places if jars aren’t clearly marked. A well-run storage shelf shows careful handwriting, best-by dates, and hazard symbols where needed. Lost labels lead to guessing games nobody in a lab ever wants to play.

Cotton gloves and safety glasses aren’t just for looks, even if the powder appears harmless. I once saw someone rub their eyes after handling potassium sodium tartrate, which led to an uncomfortable trip to the eyewash station. Direct contact dries out skin, and splashes can irritate eyes or nasal passages.

Dust escapes easily when moving this powder, especially in a fast-paced workspace. Pouring quickly kicks up clouds, which end up coating nearby benches or floating through the air. Taking a minute to transfer the powder slowly, using a scoop or funnel, cuts down on mess and risk.

Sometimes, potassium sodium tartrate mixes with more hazardous reagents. Cross-contamination poses more risk than most realize. Using separate tools—just like cooks use different knives for meat and vegetables—keeps everything safer.

Potassium sodium tartrate brings value to many industries, but simple missteps make accidents more likely. Focusing on basics—sealed storage, dry spaces, cool temperatures, and accurate labeling—has paid off in every setting where I’ve seen the compound used. Handling goes smoother with gloves, goggles, and slowly measured movements. Team training and posted reminders near storage shelves keep good practices from slipping.

Accidents almost always follow rushed or sloppy work. A few minutes of care up front beat hours of cleanup or costly product losses week after week. Respecting both the risks and benefits of potassium sodium tartrate means less waste and a safer environment.