Factories first started producing sodium gluconate on an industrial scale in the early 20th century. Demand came from textile finishing and metal surface cleaning, especially in the years just before and after World War II. The molecule’s roots reach back to the kind of applied chemistry that looked for practical answers. Chemists figured out that glucose oxidation in a microbial fermentation bath often produced gluconic acid and its derivatives. Soda was then added to make the sodium salt form stable and easy for transport. Manufacturers kept ramping up output as detergent and construction industries expanded after the war, cementing sodium gluconate’s status as a go-to additive. As chemistry labs started sharing what worked, food, cleaning, and even medicine started using it too.

Sodium gluconate appears as a white, crystalline powder. This product dissolves easily in water and goes nearly unnoticed by taste buds. It doesn’t throw off pH much, giving manufacturers more freedom when tweaking formulas. Industries have leaned on it for decades because it can help remove stubborn minerals, soften water, stabilize mixtures, keep metals from making trouble, and even preserve color and flavor. The construction sector relies on it in high-strength concrete mixes, letting projects stretch far beyond what old school recipes allowed. Water treatment facilities value its ability to hold on to trace metals without introducing safety worries. So whether it lands in a cement truck, food production line, or a detergent plant, sodium gluconate has become a regular tool.

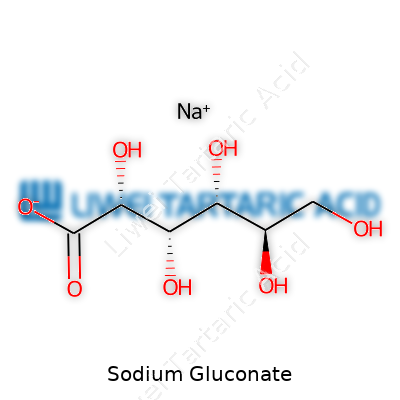

Sodium gluconate shows up as small granules or a free-flowing powder, dry to the touch and lasting on the shelf for years if it stays sealed in a cool, dry place. Chemically, it forms from gluconic acid and sodium carbonate or hydroxide. The molecular formula is C6H11NaO7, with a molar mass just north of 200 g/mol. It carries strong chelating ability, locking onto calcium, iron, and other ions that like to form scale or sludge. Water soaks it up quickly. Despite its power, it stays gentle for most uses, rarely causing a spike or crash in pH. Heat doesn’t break it down easily, and it rides out acidic or alkaline conditions with little drama.

In most markets, a food or pharma-grade product has to hit 99% purity, with strict limits on heavy metals and microbial contamination. Containers often carry precise batch numbers and best-before dates, with handling instructions that warn against contact with moisture. Labels spell out whether it’s certified for halal, kosher, or vegetarian use. In construction grade, companies might accept around 98% minimum purity, with some tolerance for certain physical properties like flow and density. Firm rules define what counts as a contaminant. Many factories use HPLC, spectrophotometry, or titration for in-house checks. For consumer trust, it pays to show detailed origin, lot tracking, and handling advice on every batch.

Bacterial fermentation sits at the core of industrial sodium gluconate production. Typically, glucose syrup feeds into fermenters holding strains like Aspergillus niger or certain Pseudomonas types. These microbes oxidize glucose into gluconic acid using aerobic conditions. Air keeps bubbling through the reactor, keeping the process moving along. After a set time, workers filter out biomass, then adjust the pH upward by adding sodium carbonate or sodium hydroxide. This neutralizes the gluconic acid straight to sodium gluconate. Removing water then yields a solid, which goes through additional purification and drying. Most plants run this nearly nonstop—some even capture and reuse waste heat. The method blends biochemistry and chemical engineering, showing off decades of process optimization.

Sodium gluconate enters plenty of reactions—rarely as a star, more as a helper. It grabs onto metal ions, making them easier to work with or keeping them quiet during mixing. That chelating skill makes it a friendly sidekick in formulas for dishwashing, water softening, and even medicine. In strong acid or base, it resists breaking down. Despite this resilience, chemists have tried modifying the molecule for better fit in different jobs. Some tweak its side chains to encourage new reactions or slower release in medicine. With metal ions, sodium gluconate sometimes prompts precipitation of secondary compounds that workers can reuse or sell for new processes. The core molecule itself remains stable under pressure, high temperature, or UV light, making it a reliable backbone for specialty blends.

On labels and in trade, sodium gluconate might wear names like “monosodium salt of gluconic acid,” “sodium D-gluconate,” or even “E576” in European food circles. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry lists it as “sodium (2R,3S,4R,5R)-2,3,4,5,6-pentahydroxyhexanoate.” You’ll spot it under branded names in construction admixtures, cleaning product ingredient lists, and water treatment catalogs. The product turns up in specialty stores as a food additive, carrying plain language names so customers know what they're getting.

Strict regulatory standards keep sodium gluconate in check, especially for foods and sensitive applications. The US Food and Drug Administration generally recognizes it as safe (GRAS), so long as manufacturers stick to the rules. Handling guidelines in workplaces focus on dust exposure, since breathing in powders never did anyone any favors. Proper storage keeps it away from moisture—which can kick off slow degradation—or incompatible substances. Workers lean on gloves and local ventilation, just as they would with other dry chemicals. Waste disposal routes usually run through standard drains when diluted, but most plants urge minimal discharge and encourage recycling when possible.

Concrete and mortar plants around the world add sodium gluconate to delay setting times, especially on hot days or in massive pours where quick hardening leads to cracks. Textile factories use it to soften water, letting dyes stick evenly and colors pop. Detergent makers prize its ability to seize stubborn metal ions, so soaps and cleaning solutions don’t leave streaks behind. In food labs, chemists call on it as a stabilizer, acidity regulator, and even to keep canned vegetables looking fresh. Medicine bottles list it as an excipient—helping active ingredients dissolve, mix, or last longer on the shelf. Water treatment facilities reach for it to grab iron, magnesium, and manganese out of the way, making filtration smoother and protecting pipes. Across industries, it shows up whenever stability and cleanliness matter.

Researchers keep asking how sodium gluconate can stretch further. Materials science teams look for ways it can help fiber-reinforced mortars or new types of bioplastics. Food tech firms invest in trials for low-sodium diets, betting that the gentle taste and solubility of this molecule helps reduce standard salt without sacrificing flavor. Pharmaceutical science still probes its potential as a carrier for trace minerals, delivering iron or zinc without tricky side effects. Bioengineers tune fermentation setups for higher yields or lower costs—sometimes swapping bacteria or fungi to cut waste. Academics test new purification steps, chasing environmental improvements and pushing production to even more sustainable models.

By most expert accounts, sodium gluconate doesn’t threaten consumers or workers when handled smartly. Studies in lab animals show low acute toxicity even at high doses, with most researchers noting quick elimination from the body. Chronic exposure testing doesn’t reveal organ buildup or cancer risk. Allergy reports land rarely, mostly surfacing in settings where people breathe in powder directly. Human clinical trials for pharmaceuticals back up the general safety narrative, so long as doses stay within limits for excipients. Environmental impact studies rate it favorably, since it breaks down in sewage treatment without toxic residue. The overall toxicology picture lets people use it widely without losing sleep about hidden risks.

Sodium gluconate will likely keep growing in demand as industries turn to greener, more sustainable chemicals. The construction boom in Asia and the push for durable, eco-friendly materials point straight to growth in this sector. Circular economy advocates see it as a smart choice because it’s made from renewable plant sugars. Plant-based fermentation aligns with the worldwide drive to slash petroleum ingredients from everything possible. Bioplastics, battery tech, and precision agriculture all circle the molecule in new research. Regulatory trends favor ingredients with strong safety records and proven biodegradability, putting sodium gluconate on solid footing. With ongoing investments in fermentation efficiency, future market forces should keep its price in reach for projects big and small.

Factories, construction sites, and water treatment facilities use all sorts of chemicals. Sodium gluconate holds an important role, even though it doesn’t get flashy headlines. I’ve seen this material up close—an easy-to-handle powder that mixes smoothly into everything from cement to detergents. Its secret weapon lies in its chelating strength, which means it grabs onto minerals like iron and calcium and keeps them in solution. This makes a world of difference in industries that wrestle with hard water or reactions that gum up equipment.

In concrete mixing, sodium gluconate’s effect stands out. Concrete needs time to harden right, especially in hot climates. By slowing down the setting reaction just enough, workers get a few more precious minutes to finish the job without rushing. This can save money on labor and stop costly mistakes. Data from civil engineering studies shows that concrete treated with sodium gluconate often sets more evenly and reaches a stronger finished state. That’s not just helpful; it builds safer buildings.

Walk through any industrial laundry or commercial dishwasher operation, and you might find sodium gluconate on-site. It stops minerals in the water from scaling up pipes and gears. Hard water slows down cleaning equipment and leaves spots that people complain about. Sodium gluconate grabs hold of those minerals, letting the machines do their job and stay out of repair shops longer. Factories save on maintenance bills and keep production lines moving.

Municipal water treatment plants also use this compound. City water contains all sorts of impurities, and old water pipes corrode faster when minerals settle out. Sodium gluconate keeps these minerals dissolved, which helps water flow smoothly through city pipes without clogging. Residents don’t think about it, but that means cleaner water and fewer service breakdowns.

One point about sodium gluconate deserves notice: Its safety profile looks good by chemical standards. Regulatory bodies have reviewed its toxicity and labeled it as generally safe for workers and the environment, as long as companies follow normal precautions. Biodegradability matters, too. Sodium gluconate breaks down without leaving behind heavy metals or tough pollutants that linger in soil and water. Many companies look for ways to cut their environmental impact, and swapping out harsh chemicals for safer ones like sodium gluconate gets recommended by groups focused on sustainability.

Some might worry about cost and efficiency. Sodium gluconate costs a bit more than old-school chelators. In tight markets, budget managers push back on upgrades. But evidence shows the long-term savings in maintenance, fewer machine breakdowns, and better final products often balance out the price. Training for workers helps, too. Teams who understand how and when to use sodium gluconate don’t waste it.

From mixing cement to making sure tap water tastes right, sodium gluconate does some heavy lifting behind the scenes. Looking for safer chemicals that work well while lowering maintenance costs makes sense in both industry and everyday life.

Sodium gluconate turns up in ingredient lists for a bunch of processed foods, especially those with sauces, seasonings, or dairy flavor. It works as a stabilizer, keeps things from clumping or spoiling, helps certain foods hold their color, and sometimes masks bitter flavors. This compound is a sodium salt of gluconic acid, and you’ll also find it in cleaning supplies and water treatment. Its food uses make people wonder about its safety, especially as more folks seek to limit mystery additives.

Regulators in Europe, the United States, and Canada all allow sodium gluconate in food. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration places it in the “generally recognized as safe” column, which isn’t just a rubber stamp — scientists have reviewed studies relating to its structure, how bodies break it down, and possible toxicity. Food authorities in the European Union and Canada reached similar conclusions: no evidence shows it causes harm at the levels people actually eat.

The sodium part raises concern for anyone watching salt intake. Sodium gluconate delivers sodium, but in much lower amounts than table salt does, unless someone pours on the ultra-processed food. In studies, animals given high doses show no ill effects. In humans, even sensitive groups do not report allergies or intolerance. Still, no food additive deserves a free pass, and moderation matters for almost everything on the shelf.

People have a right to be skeptical about chemical-sounding additives. At the supermarket, food labeling doesn’t always spell out what these ingredients actually do. Parents, especially, lean cautious if a product has a complicated chemical name. For me, growing up with family members who struggle with allergies, every odd-sounding word made us hit the search engine — many families do the same. Big headlines about harmful ingredients in packaged foods only add to the anxiety, even if the science paints a different picture for sodium gluconate.

If you aim to eat whole foods, sodium gluconate mostly stays off the table anyway. It sits in the toolkit for manufacturers stretching shelf life or keeping salad dressing creamy. A lot of health-conscious folks scan labels for any unnecessary extras, and I’ve done the same, choosing simple ingredient lists whenever possible. Individuals with chronic kidney issues should be cautious about overall sodium content in foods, so sodium gluconate falls under the same category as other salty additives.

Sodium gluconate doesn’t appear to trigger intolerance, allergies, or digestive problems. The body efficiently breaks it down and flushes it out. Still, ingredient transparency matters. If a label confuses, most food companies respond to questions about additives — sometimes just getting a clear answer from the source eases any worry.

Anyone worried about additives can start by limiting ultra-processed foods and choosing meals built from fresh sources. Reading up on ingredient lists, asking direct questions of manufacturers, and discussing any new symptoms with a healthcare provider can go a long way. Thanks to oversight from agencies and available research, sodium gluconate looks about as safe as other already-approved food additives. Still, real knowledge comes from staying curious and weighing the facts as research grows.

At the heart of everyday products like cleaning agents and water treatments, sodium gluconate helps things work better behind the scenes. The basic building blocks of sodium gluconate show up as its chemical formula: C6H11NaO7. You get this compound when gluconic acid reacts with sodium hydroxide. The process forms a salt, with sodium coming from the alkali and gluconate stemming from the naturally occurring acid, which itself springs from glucose, the simple sugar found in fruit and plants.

Seeing a chemical formula like C6H11NaO7 might not light up everyone’s day, but hearing how this stuff pulls its weight around the house or factory changes the picture. Many people scrubbing stubborn stains or working in construction probably don’t know how much they rely on sodium gluconate. In cleaning products, it wraps itself around hard water minerals so they can’t leave residue or mess with detergents. In concrete, it makes things more manageable, stopping the mix from setting too fast. That extra working time translates to stronger, longer-lasting buildings.

Doctors, engineers, and food technologists pay close attention to chemical formulas because the structure shapes the function. Sodium gluconate owes its power to the combination of six carbons, eleven hydrogens, one sodium, and seven oxygens. Having these atoms organized the way they are means the molecule grabs onto calcium, iron, magnesium, and other metal ions. Water with metal ions might taste odd or mess up equipment and food processing, but sodium gluconate catches them, keeping things running smoothly. That’s especially helpful in hospitals sterilizing equipment or companies preparing pharmaceuticals, where pure water isn’t just nice to have—it’s essential.

Speaking from experience working around pools and greenhouses, handling chemicals always pushes you to look past the basics. Sodium gluconate stands out as relatively gentle, both for people and the planet. It breaks down easily and doesn’t hang around in the environment. Compared to harsher alternatives, using sodium gluconate can mean less chemical runoff and fewer long-term headaches for water systems and wildlife. The FDA recognizes its safety in food and personal care, a reassuring stamp for families who prefer not to puzzle over product ingredients. For industries, that trust allows for easier adoption without mountains of red tape.

Reliance on any one additive brings up questions about supply chain, price, and the risk of overuse. Markets fluctuating or demand spiking can drive up costs, squeezing smaller businesses. Manufacturers can invest in research to make production more efficient, perhaps drawing from waste streams or renewable resources. Teaching the public and industry teams about proper use helps make sure sodium gluconate delivers results without waste. Some regions experiment with homegrown sources of gluconic acid, hoping to ease the pressure on global supply and boost local economies. Innovation also comes from pushing for even safer, milder alternatives in the future, but sodium gluconate holds out as a solid example of chemistry done right—with the right balance of science and common sense.

Many additives move between food and industry, blurring lines we think should be clear. Sodium gluconate is one of those. I’ve seen this ingredient in bakeries, where it helps dough relax and improve texture. I’ve also watched it work wonders in concrete mixing yards and bottle-washing plants, cleaning and keeping things from sticking together. That kind of dual life makes people raise questions about where it truly belongs.

Sodium gluconate finds its way into a surprising list of processed foods. Food factories use it to keep colors bright, stabilize mixtures, and bind minerals. It manages to act without bringing off-flavors or strange aftertastes. The FDA has given it the green light as safe, and you’ll spot it on labels under “food additives”—sometimes as a sequestrant or acidity regulator. Seen it in cheese spreads, perhaps a snack cake or two? I have. Without it, some products just don’t hold up on shelves or taste the same week to week.

Industrial use, though, doesn’t look anything like what happens in a bakery or dairy. In construction, sodium gluconate keeps cement from setting too fast, especially during a hot summer pour. It grabs hold of metal ions, which matters whether you’re cleaning bottles in a soda plant or treating water to keep pipes from corroding. I remember chatting with a maintenance engineer at a waterworks, who swore by it for stopping scale buildup. Here, food safety isn’t top of mind—the focus is on performance and cost.

Some folks see a chemical name and get nervous, especially when it jumps from lunchbox to factory floor. I’ve heard people wonder if using the same chemical in both fields points to shortcuts or undisclosed risks. History tells us that cross-over isn’t rare: vinegar, citric acid, and vitamin C all play in both spaces. The question, then, is about oversight. Are both grades really held to the right tests? In food, purity is non-negotiable. Industrial batches can contain impurities that don’t pass food standards. Producers sell food-grade lots for kitchens, and a separate supply for factories. That divide matters.

Trust depends on how well companies separate and label these products. No one wants industrial leftovers in dinner rolls. Regulators like the FDA and EFSA keep an eye on both markets. I believe they should double down on random testing, not just paperwork checks. More than that, brands ought to explain their sourcing and quality steps in plain language. Let people see certifications and traceability. On the factory floor, managers must avoid mix-ups with storage and transport.

For most people, sodium gluconate in their food isn’t a looming danger. Long-term studies haven’t turned up health scares at doses used in food. I watch for brands that talk openly about their ingredient suppliers and share lab test results. That openness counts for me, especially when I buy something my kids will eat.

Better oversight and clearer labels help everyone share confidence. New techniques can separate food and industrial streams more reliably, using QR codes on packaging and tamper-proof seals. The next step is making sure every part of the supply chain follows rules meant for human safety, not just price or convenience. In my view, that’s the way to let ingredients like sodium gluconate serve both their jobs without crossing the lines that matter most.

Anyone who’s handled chemical additives, especially ones used in construction or food processing, knows that storing them is far more than a technical box to check. Sodium gluconate seems like a humble white powder, but once it absorbs moisture it clumps, cakes, or loses its punch for whatever job you’ve got lined up. Ask anybody who’s opened a soggy bag left near a leaky roof – the frustration is real.

So the first thing to get straight: sodium gluconate must stay dry. Storage in a cool, well-ventilated area gives you the best shot at quality over the long haul. Make sure air can move around, pushing away humidity instead of letting it gather. If you’ve worked in a hot, muggy warehouse, you’ll know this is easier said than done. Good practice involves racks off the floor and bags on pallets, away from any water lines, AC condensation, or drafty windows.

Food processing folks with years in the business will tell you, storing any product that ends up in something people eat calls for spotless conditions and zero cross-contamination. Sodium gluconate used as a food additive or cleaning ingredient can lose certifications fast if the storage environment allows debris, pests, or residue from other chemicals to creep in.

At the warehouse I managed, we scheduled quarterly deep cleans, swept daily, and left no opened bags sitting around. Every sealed package should have a clear batch label and use-by date so teams don’t guess which pallet to use next. Keeping sodium gluconate away from chemicals like acids matters: direct contact could trigger messes or technical issues in your end product.

Anyone who’s had chemical products spoil from heat waves knows the value of a stable, moderate climate. Ideally, stay under 25°C (77°F). High temps or wild swings cause ingredients to degrade or react in unpredictable ways. In places without advanced HVAC, some companies use shade cloths, ventilated storage sheds, and regular temperature checks. Using reusable airtight containers beats cut-open bags every time in humid climates.

Storing food- or construction-grade materials comes with tight rules. The FDA, EFSA, or local agencies all watch for missteps. Labels need to stay legible and original packaging should not be tampered with. Have staff sign off on any movement of product, inspect for tampering, and document temperature and humidity readings during storage. At my old job, catching a leaking pipe saved two shipments and thousands of dollars. Tell your team: if something looks off, report it; don’t wait.

Store only what you can reasonably use in the next six months unless your facilities match all the best practices for long-term storage. Rotate stock so older bags get used before new deliveries. Patch leaks and fix insulation for savings and better product retention. Finally, keep records. If problems appear—odd clumping, color changes, dampness—you’ll have a timeline to trace issues to their source.

Simple, practical storage steps go a long way toward keeping sodium gluconate effective and in compliance with food safety or construction standards. A little effort up front prevents bad product, expensive waste, and a lot of future headaches.