Potassium gluconate didn’t start out as a drugstore supplement you toss in your basket after a doctor’s nudge to mind your electrolytes. Tracing its roots back to early twentieth-century chemistry, scientists searched for ways to make minerals like potassium more bioavailable without painful side effects or the harsh taste that often kept people from swallowing their medicine. The gluconate form comes from a reaction with gluconic acid—a hint at how pharmacy and food science often mesh. As medicine shifted from rough-hewn powders to recognizable tablets and capsules, food additive makers and supplement formulators saw how potassium gluconate served up a solid bet for those with dietary gaps or heart health risks. Today you’ll spot it just as easily in oral rehydration solutions as in certain food fortifications—evidence of chemists’ success in marrying safety, taste, and reliable dosing.

Potassium gluconate shows up on ingredient lists as a source of the essential mineral potassium. It delivers both the needed element and a gentle organic acid, sidestepping many of the gastrointestinal hurdles seen in other potassium salts. In supplement aisles or pharmaceutical catalogs, shoppers find it as a tablet, capsule, or bulk powder—sometimes mixed into sports drinks. Food industry chemists work with it to adjust mineral content in prepared meals. No shelf-watcher would call it glamorous, but for anyone short on potassium, this simple compound offers a practical solution without the sharp tang or irritation of other options.

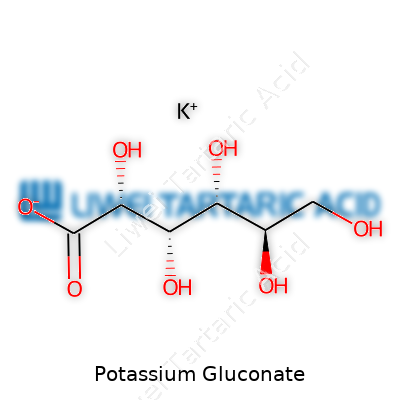

Potassium gluconate appears as a white or off-white crystalline powder, easy to mistake for common salt. It dissolves calmly in water, forming a clear solution. Unlike many mineral compounds, it resists clumping in humid air. Chemically, it holds one potassium atom for every gluconate group—C6H11KO7 by formula, weighing in at around 234 grams per mole. Its gentle nature arises from that large gluconate ion, which tames potassium’s natural tendency to irritate. Tasting mildly sweet, the substance avoids the sharp metallic taste typical of inorganic potassium compounds. Its melting point stays above 180°C, and under normal storage, it keeps stable for years, provided it avoids moisture and high heat.

Labels usually mention potassium gluconate’s purity, pointing toward pharmaceutical or food-grade standards. Content claims specify potassium’s weight percent or milligrams per serving—important since only part of the powder delivers the mineral. Official compendia demand low levels of heavy metals and contaminants. In nutrition panels, manufacturers mark actual elemental potassium content: in a 595 mg tablet of the compound, users get just 99 mg of elemental potassium. This level sits below the FDA’s over-the-counter potassium limit set for safety, so attentive dosing and clear communication help keep users on firm footing.

Producers make potassium gluconate by neutralizing gluconic acid—typically derived from glucose oxidation by certain microbes—with potassium hydroxide. The reaction forms the salt and a little water. The product crystallizes from the remaining solution, then filtration and drying leave the finished compound. The careful control of both ingredients and process ensures purity. Pharmaceutical suppliers often extend testing to include microbiological checks, knowing that impurities or residual solvents could taint even such a seemingly mild mineral supplement.

Under standard use, potassium gluconate doesn’t put up much of a chemical fuss; its value comes from its gentle dissociation into potassium and gluconate ions in the human gut. In research settings, some tinker with the molecule, creating derivatives by modifying the gluconate group, chasing after new delivery systems or time-release properties. In highly alkaline or acidic conditions, doctors or chemists understand that breakdown can occur, forming byproducts like potassium carbonate and smaller acids. Nothing too exotic, but consistent batch quality relies on close monitoring.

Potassium gluconate carries other names, depending on the label or industry. Retailers call it “potassium salt of gluconic acid,” “glukonat de potasio” in Spanish, or sometimes just “K-gluconate.” These aliases spring from international naming conventions and regulatory listing requirements. In technical documents or food additive codes, it sometimes appears as INS number 578. Older pharmacopoeias mention the Latin “kalium gluconicum,” while veterinary catalogs may list it under a slightly different set of product codes. Through every guise, the molecular framework stays the same, carrying out its mission of safe potassium delivery.

Safety stands as the primary focus when supplementing with potassium. Doctors—myself included, working in clinics—work from clear guidelines. Overdosing on potassium, even in mild forms like the gluconate, runs the risk of disrupting heart rhythms, sometimes with fatal consequences. The FDA limits non-prescription potassium supplement servings to 99 mg elemental potassium, precisely to head off these dangers. Food-grade and pharmaceutical batches run through rigorous heavy metal tests, microbial screens, and purity checks. On the packaging side, clear dosing instructions, allergy warnings, and batch traceability form non-negotiable requirements. Employers training staff on handling encourage strict adherence to hygiene and proper gear; accidental spillage or ingestion outside control protocols could spark health or liability issues.

Potassium gluconate found its foothold in the world of human and veterinary supplements. Heart patients managing hypokalemia rely on it as a safe and palatable way to replace potassium lost from diuretics. Sports nutrition companies blend it into formulas targeting long-game endurance athletes who sweat out minerals in liters. Animal feed operations sneak it into pellets to balance rations for high-yield dairy operations or egg-laying flocks. Hospitals use it in IV solutions, calculated down to the last milligram, while food technologists lean on its stability for milder fortified foods. In personal experience speaking with patients, I find those who struggle to find potassium in their diets appreciate how easily this supplement slips into daily routines.

R&D labs see potassium gluconate as both a simple mineral source and a starting point for more complex health solutions. Current projects target controlled-release forms—the kind that maintain steady potassium levels in blood over hours instead of sharp peaks and drops. Pharmaceutical engineers tweak the gluconate base to attach other molecules, building new compounds or enhancing absorption. In the food tech world, scientists analyze how enriched foods with potassium gluconate affect taste or shelf life. These advances come out of partnerships between university chemistry departments, supplement companies, and clinical trial centers, all hungry to balance safety, cost, and absorption in future supplements.

Potassium’s double-edged reputation turns up under the toxicologist’s microscope. At normal doses, potassium gluconate doesn’t raise alarm bells—the body tightly regulates potassium, and healthy kidneys excrete what isn’t needed. But for people with kidney trouble, or those who down handfuls of supplements, blood levels can climb, risking dangerous heart issues. Published studies in journals like Clinical Toxicology confirm the safety of recommended doses while naming “hyperkalemia” as the chief risk from overuse. Animal models and clinical case reports inform every label warning and physician-patient talk. Poison control lines still cite supplement-related potassium toxicity as rare, as long as people stick to dosing guidance.

Potassium gluconate’s future rests on growing demand for safe mineral fortification. As trends shift away from high-sodium diets, more brands look for ways to boost potassium without scaring off consumers with bitterness or hard-to-pronounce ingredients. For me and other practitioners, this points to expanded use in hospital nutrition, senior diets, and even school lunch initiatives. Researchers continue eyeing time-release forms and combinations with other trace minerals, hoping to go beyond simple supplementation into precise, personalized mineral balancing. As understanding of electrolyte health deepens, potassium gluconate will likely cement its place in medicine cabinets, sports drinks, and global health strategies. Every new study and regulatory update feeds into a pipeline that, frankly, needs this kind of unassuming, reliable compound.

Potassium drives a lot of daily body functions, especially in places you rarely think about. Your heart’s steady beat, muscle work, and even nerves counting signals all draw on potassium. Potassium gluconate stands out because it steps in where diets fall short. Bananas, potatoes, spinach—they get praised for potassium, but sometimes life’s busy mix makes it hard to eat enough of them. Supplements step up to fill that gap.

I remember coaching a local running club. Some folks, even the ones eating what looked like healthy foods, felt tired, had leg cramps, or just couldn’t get their energy back. Their blood tests told the story: potassium levels scraping the floor. Doctors call this hypokalemia. It gets dangerous if it’s not spotted. Heart rhythm gets tossed off and muscles start twitching or refusing to work. Potassium gluconate steps in because it’s easier on the stomach than other options and helps nudge blood levels back to normal.

Doctors often talk up potassium for blood pressure control. Evidence backs them. Research from the CDC and American Heart Association ties steady potassium intake to lower blood pressure, which lowers risk of stroke and heart trouble. Not everyone needs supplements—lots of Americans get enough from food. Still, folks with certain prescriptions, kidney issues, or specific diets can fall behind. Potassium gluconate offers an easy fix in these situations.

Some people might look at a bottle and think, “Just a supplement, it must be safe.” Experience tells a different story. Checking with a doctor before taking potassium makes all the difference, especially for folks on water pills or with kidney conditions. These bodies handle potassium in a unique way, and too much can land you in the hospital. People with normal kidney function, following medical guidance, find potassium gluconate useful for topping up daily needs.

Clinical studies keep showing potassium’s benefits. A review from 2022 in The New England Journal of Medicine reported lower blood pressure in people using potassium supplements. Potassium gluconate works partly because it dissolves well and doesn’t upset the stomach as much as other kinds. Safety always depends on dosing and regular checkups, since too much can harm the heart or kidneys.

It’s tempting to rely on pills. Food still builds a stronger base. Foods like beans, melons, sweet potatoes, and leafy greens not only bring potassium but come packed with fiber, vitamins, and minerals you won’t find in a tablet. Potassium gluconate gives a safety net for people who need it, especially those balancing health conditions or tough schedules. Asking questions at the clinic and staying curious about what your body needs is what really keeps health on solid ground.

Potassium isn’t some mystery mineral. It keeps the heart beating, muscles moving and nerves firing off the right messages. Still, too little or too much of it can throw everything off. Most of the time, people hear about potassium in bananas or leafy greens. Potassium gluconate comes up when someone really needs a boost—maybe because of certain medications, kidney issues or strict diets.

Potassium gluconate can fix a deficiency fast, but some folks run into side effects. Many don’t report problems, but others get stomach aches, loose stools, or nausea. As someone who once tried a supplement to fight off muscle cramps, I dealt with a few queasy mornings. It passed, but made me question if a supplement was worth it for occasional leg pain instead of changing up my meals.

Doctors usually warn about one big risk: taking too much. Mild issues include stomach upset, but folks who have pre-existing kidney trouble can get into deeper water. High potassium in the blood, known as hyperkalemia, triggers irregular heartbeats, tingling, or sudden muscle weakness. In rare cases, it brings the risk of heart stoppage. A 2021 report in the New England Journal of Medicine drives this home—patients with severe hyperkalemia had more than double the risk of sudden death.

Potassium supplements like gluconate aren’t for everyone. Diuretics, ACE inhibitors for high blood pressure, or certain anti-inflammatory medications all change how much potassium sticks around in the body. Folks with chronic kidney disease run a real risk since their kidneys can’t flush out extra potassium. Even the healthiest athlete can find trouble if they stack high-potassium supplements with potassium-rich foods.

Healthcare guidelines, like those from the FDA and Mayo Clinic, recommend that folks talk to their doctor before touching any supplement with added potassium—especially if there’s a medical history in the picture.

Honestly, most mild issues clear up after a few days or a dose change. Nausea that lingers, ongoing diarrhea, or stomach cramping should send someone back to the doctor’s office. Any signs of confusion, chest pain, shortness of breath, or a heartbeat that feels strange should get checked out right away. Those aren’t small side effects, and pretending they’ll just pass puts health on the line.

Doctors usually suggest starting with food to manage potassium. Avocados, spinach, white beans, and oranges all pack plenty and are much less likely to cause sudden shifts than pills or powders. Blood tests can help guide any needed supplement changes. In my own case, swapping in more potatoes and yogurt helped handle cramps better than supplements ever did.

Potassium gluconate isn’t the villain, but treating it like a harmless vitamin creates problems. Anyone thinking of using it for more energy, fewer cramps, or a healthier heart needs a plan—and a good doctor in the loop. Supplements work best with real knowledge about what the body needs, not guesswork.

Potassium helps nerves, muscles, and the heart keep moving along. A body that dips too low in potassium gets tired, weak, and may end up facing heart rhythm trouble. In my years working around hospitals, I’ve seen that something as simple as dehydration or too much sweating can tip the balance fast, especially in older adults or folks with chronic illness. Blood tests catch drops early, but the right supplement makes a difference in staying healthy.

No over-the-counter bottle should replace a conversation with your doctor. Potassium changes the way medicines work—especially water pills, blood pressure drugs, or heart medication. Most people get enough potassium in their diet by eating fruits and veggies, but disease, vomiting, or medications can mean you need a supplement. Doctors check your blood, run through your meds, and decide if you even need potassium. No need to self-prescribe and guess at an amount—too much or too little, both cause problems.

The most common way to take potassium gluconate comes as a tablet, liquid, or powder. Always swallow tablets whole with a full glass of water. Crushing or chewing can send a dose straight to your stomach lining, and that burns. Liquid or powder needs the right dilution; mix it well in a glass of water or juice. Take it with food. An empty stomach often leads to cramps or nausea, and there’s nothing worse than losing your appetite over a pill that’s supposed to help.

I’ll never forget one patient who mixed up extra-strong liquid with his water because nobody explained how concentrated it was. Symptoms hit fast: tingling arms, a strange heartbeat, and mild confusion. Lower, steady doses over several hours or days work best. Setting a daily routine—maybe at breakfast—helps avoid missed or mixed-up doses. If you miss a dose during the day, just pick up where you left off. Don’t double up. Doubling leads to unnecessary swings in potassium levels, and that carries its own danger.

Potassium gluconate upsets stomachs, so take it with food unless your doctor says otherwise. If your stomach hurts, tell your provider. Sometimes a different formulation helps, like liquid or a slow-release tablet. Watch for muscle cramps, new weakness, or irregular heartbeat. A high potassium level builds quietly, and side effects sometimes look like low potassium: tiredness, heart flutter, or numbness.

If you notice anything off—never trust Google guesses—call your medical team. The only sure way to check potassium is a blood test. People with kidney issues, diabetes, or an adrenal gland disorder need extra medical guidance. Potassium pills work only if your body can process all that extra mineral.

Food often helps more than pills. Bananas, potatoes, spinach, lentils, and oranges give steady potassium without the spikes. If you need a supplement, stick with the plan you and your provider set. Use a pillbox or phone alarm. Let your pharmacist know about all your prescriptions and supplements. Mixing many medicines bumps up the chance of side effects.

Potassium won’t fix every ache or cramp. Listen to your body, check with your doctor, and don’t get caught up in supplement fads. Real health comes from steady habits, not quick fixes.

Mixing supplements and medications never feels simple. Doctors and pharmacists spend years piecing together knowledge about drug and supplement combos, and even then, new discoveries keep us on our toes. Potassium gluconate, usually taken to correct low potassium, sits in that category people tend to underestimate. From my own days managing prescriptions behind a pharmacy counter, the questions around mixing potassium with other meds cropped up more often than you might think.

Potassium keeps muscles, nerves, and your heart beating on time. Diet alone doesn’t always provide enough—especially for folks taking water pills or certain blood pressure medications. It’s tempting to reach for a supplement and hope for the best, but that can backfire without some careful thought.

Take some of the most common pills: ACE inhibitors, like lisinopril, or potassium-sparing diuretics, such as spironolactone. Mix in potassium gluconate, and you risk pushing potassium levels too high. I’ve seen patients develop weakness, confusion, or even abnormal heart rhythms. People often hope a supplement will offset other medication effects, but sometimes the mix causes more harm than good.

Adding over-the-counter pain meds like NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen) to the mix can sneakily boost potassium, especially for those with kidney problems. Folks with diabetes or heart failure should tread carefully—both groups already struggle with potassium balance.

People read drug facts, try to piece together the puzzle, and figure it's safe to add a supplement. It’s easy to miss the fine print about hidden potassium in salt substitutes, multivitamins, or sports drinks. Most people think about only the main prescription meds, ignoring everything else. All those sources add up.

We're not talking about a rare allergy or an unusual side effect. Potassium, in the wrong amount, can knock the heart out of rhythm. No dramatic symptoms warn you every time. Sometimes the only clue is an EKG change or a blood test showing trouble. Several times I've seen doctors run that potassium test after a patient lands in the ER—by then, symptoms have already rolled in.

People should talk things through with their doctor or pharmacist before mixing potassium gluconate with anything else. A quick chat saves a world of worry. I’ve suggested simple tools, like writing down every pill and supplement, looking up potential interactions, or even sticking with more potassium-rich foods instead of a pill.

Education changes everything. Doctors watch for red flags, like signs of kidney trouble or meds that affect potassium, but the patient plays a role too. Checking in before starting something new strengthens safety. Labs help keep tabs, especially after a medication change. Information from places like the FDA and Harvard Medical School supports what many of us have seen: supplement safety depends as much on teamwork as science.

Potassium supplements might seem harmless, but the heart won’t always agree. Mix medications or try to fix a dietary gap without real guidance, and you invite risks. Better to ask the right questions, check in regularly, and respect how tightly our hearts cling to balance. The safest option comes from good conversations, not guesswork.

It’s easy to see why some people reach for potassium gluconate as a supplement. You hear about its benefits for nerve and muscle function, and how it supports the heart. The story’s bigger than just the good side, though. Potassium works best when your body stays in balance, and a supplement doesn’t always solve the problem. In some cases, it actually causes new issues.

Folks living with kidney disease already struggle to keep potassium regulated. The kidneys act as filters, and when they slow down, extra potassium lingers. According to the National Kidney Foundation, high potassium levels in those with kidney impairment can trigger dangerous heart rhythms or even stop the heart. Potassium builds up slowly. Sometimes people won’t notice anything’s wrong until they feel numb or weak, or notice a weird heartbeat. As someone who grew up seeing a relative manage chronic kidney disease, I saw firsthand the strict diet changes and supplement restrictions, and how just one wrong move could make someone ill for days.

Doctors hand out plenty of prescriptions for blood pressure and heart failure. Some medicines, like ACE inhibitors or certain diuretics (spironolactone, amiloride), push potassium levels up. People taking these medications get regular lab tests for a reason. Extra potassium from supplements, even in small doses, makes things more unpredictable. The American Heart Association points out that high potassium can overwhelm the heart and sometimes tilt someone into cardiac arrest. People with a history of irregular heartbeats, like atrial fibrillation, don’t get much wiggle room for mistakes.

Age and diabetes both shrink the margin for error. As we get older, kidneys often lose some filtering power, which means potassium climbs higher with each dose. High blood sugar in diabetes can quietly harm kidneys over time. Even if you feel fine, unseen changes raise the risk. The CDC estimates nearly one in three adults with diabetes hasn’t even been diagnosed, which leaves some taking over-the-counter potasssium because they feel tired. A simple blood test makes a world of difference, yet many folks skip it.

Potassium hides in a surprising number of foods and multivitamins. Bananas, potatoes, leafy greens—if someone’s already eating plenty, a supplement tips the scale fast. Combining potassium gluconate with salt substitutes or multivitamins piles on the risk. Many people use magnesium or calcium at the same time, which isn’t always safe if heart or kidney function isn’t solid. Smart supplement use means looking at the whole diet, not just one label.

Potassium gluconate isn’t the right answer for everyone, even though you’ll see it on drugstore shelves. Before starting, ask a pharmacist or doctor about prescriptions, kidney health, and any recent blood work. Health teams want to help folks dodge problems before they start. In my work and with my own family, I’ve seen how simple conversations about medicines can prevent long, costly hospital trips. More education about supplements helps people make choices with both facts and real-life risks in mind.