Back in the earliest years of modern chemistry, chemists spent countless hours separating natural acids. L(+)-Tartaric acid popped up from the dregs of winemaking, discovered by scientists like Carl Wilhelm Scheele and further explored by Louis Pasteur. Pasteur’s experiments in the mid-1800s helped cement the importance of molecular chirality, and he literally plucked this compound from wine barrels—scraping crystals and using tweezers and microscopes. Decades rolled past, and industrial processes changed the scene. Cheap, reliable synthesis drew from fermentation and carbohydrate oxidation, rather than the unpredictable leftovers tucked in vintage barrels. Tartaric acid’s journey reflects how practical needs and sharp observation can launch a compound through chemistry’s front door and into everything from food to pharmaceuticals.

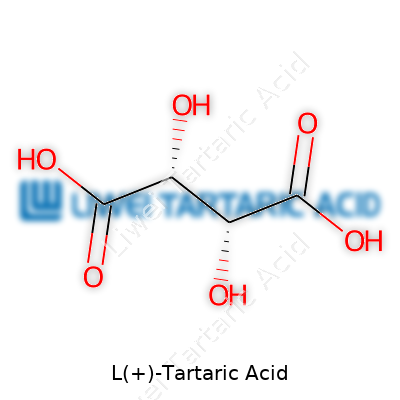

L(+)-Tartaric acid comes as a white, crystalline powder, dissolving easily in water. It wears two carboxyl groups and two hydroxyl groups, forming a backbone that's both reactive and stable under normal conditions. People find it in everyday foods, hiding in grapes, bananas, and even baking powder. As a specialty chemical, it carries plenty of industry-specific synonyms: naturally occurring L(-)-2,3-dihydroxybutanedioic acid, just Tartaric acid in food formulations, or E334 on food labels. Different industries pick their own favored name, but the function rarely changes.

This organic acid looks clean and solid at room temperature, with a melting point in the neighborhood of 170°C. It tastes sour, but not as sharp as citric acid, and it lends a decisive touch to taste, texture, and product stability. Water dissolves tartaric acid quickly; alcohols, much less so. Chemically, it resists mild oxidation but breaks down under strong heat, and its pKa values hover right for acting as a reliable acidulant or buffering agent. The combination of its stereochemistry and hydrophilic groups makes it well-suited to form complexes with metals—a reason it pops up in electroplating baths and as a stabilizer in lab protocols.

Manufacturers face rigorous demands when putting L(+)-tartaric acid on the shelf. Purity often exceeds 99.5%, and even trace metal content can draw scrutiny, especially for food, beverage, or pharmaceutical use. The main technical parameters—appearance, specific optical rotation, melting range, heavy metal contamination—are listed on global product labels and must meet regional inspection regulations from the US FDA or the European Food Safety Authority. Labeling norms also require a list of potential allergens, GMO status, country of origin, and, for certain uses, kosher or halal certification.

Industrially, most L(+)-tartaric acid comes from the byproducts of winemaking, specifically from grape must or lees. Most facilities start by isolating crude potassium bitartrate (cream of tartar), treating it with calcium hydroxide to form calcium tartrate, and then acidifying that with sulfuric acid to release the free tartaric acid. Some plants boost output through specific fermentative processes using waste from sugar production. Laboratory synthesis can involve oxidative cleavage of maleic acid or tartaric acid from carbohydrates, but these approaches rarely beat the cost advantages of agricultural feedstock.

Chemists value tartaric acid for its rich chemistry. The two chiral centers make it a template for asymmetric synthesis. It reacts with alkaline metals to create salts, like Rochelle salt (potassium sodium tartrate), prized for its use in piezoelectric devices. Intermolecular reactions can yield various esters, ethers, or coordination complexes, tuning properties for specific technical roles. Lately, research into modifications has centered on integrating tartaric acid into biopolymer formulations, where its reactive sites create linkages or crosslinks for enhanced material strength or biocompatibility.

Trade catalogues, pharmacopoeias, and food industries list tartaric acid under a broad range of synonyms. Some call it “L(+)-2,3-dihydroxybutanedioic acid”, others prefer “natural tartaric acid”, E334, or just “Tartaric acid, L form”. Product names depend on intended application: technical grade for industrial use, food grade for consumer products, and pharmaceutical grade for medical and laboratory use. These distinctions guide buyers to the right version, avoiding costly mistakes in sensitive applications.

Handling tartaric acid in bulk means respecting local regulations for chemical storage and personal safety. Contact causes irritation to eyes, skin, or mucous membranes, so gloves and goggles become routine for workers. Ingested in moderate food-grade doses, it’s safe—the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) sets an acceptable daily intake without major concerns. Large-scale chemical production facilities build procedures around containment, ventilation, and rapid spill response, since concentrated dust clouds can trigger fire or even inflammation in airways.

Food and beverage processors reach for L(+)-tartaric acid to adjust pH, sharpen flavors, and stabilize foams. It’s the backbone of baking powders where its acidity sets off the fizz that keeps cakes light. Winemakers routinely tweak acidity with it to balance taste and preserve freshness. Beyond kitchens and bottles, pharmaceutical companies lean on this acid to act as an excipient or stabilizer in drugs like effervescent tablets and injectable solutions. Metal cleaners, textile brighteners, and electroplating baths all benefit from its solubilizing and complexing prowess. Researchers pressing for greener chemical processes now look to tartaric acid as feedstock for biodegradable polymers and as a chiral building block.

Labs around the world have turned tartaric acid into a testbed for chirality-based syntheses. Research teams design new catalysts starting with its ready-made stereochemistry, searching for greener, more efficient ways to build pharmaceuticals. In agricultural science, studies dig into how tartaric acid derivatives might protect plants from certain pathogens or improve soil composition. Material scientists have tested it in bioresorbable plastics and new forms of emulsifiers. With the world’s attention shifting toward renewable feedstocks, researchers have mapped out new fermentation technologies where tartaric plays a central role, aiming to cut down waste and carbon emissions.

Decades of ingestion data show that tartaric acid, at the concentrations found in foods, carries few health concerns for the general population. Toxicity studies point to gastrointestinal symptoms only at doses way above what consumers ever reach, documenting nausea and abdominal pain in rare overdose cases. The compound’s breakdown pathways in humans involve conversion to carbon dioxide and water, so it doesn’t accumulate in organs or tissues. Modern toxicologists keep watch over occupational exposures, flagging chronic inhalation of tartaric acid dust as a risk for mild respiratory irritation. Regulatory bodies regulate its addition to food and set limits based on thorough safety profiles, regularly updating these as new evidence comes to light.

Looking forward, tartaric acid’s foothold in many industries looks pretty stable, given the growing consumer preference for natural food additives and renewable chemistry. Production methods may keep evolving, especially if grape harvests grow more unpredictable with changing climates. Synthetic biology and precision fermentation techniques could lower costs and uncouple supply from agriculture, while expanded applications—biodegradable plastics, greener corrosion inhibitors, improved pharmaceutical molecules—draw from its unique chiral structure. The intersection of chemistry and sustainability marks tartaric acid as a chemical with both a storied past and room for innovation, ready to keep proving its value beyond the vineyard.

Digging into what L(+)-Tartaric Acid actually does, I’ve come to see its importance far beyond a chemistry class. Found in grapes, bananas and even in wine, its story stretches into the foods and products we use every day. That’s something I find both surprising and a bit impressive — a clear sign we bump into science even when we’re not looking.

Anyone who’s worked in a bakery will recognize the name. L(+)-Tartaric Acid keeps baking powder active, helping bread and cakes rise. Taste-wise, it brings a tart, sour punch, especially in fruit-flavored candies and jams. I used to think that tang in lemon sweets came all from citrus, but plenty of it comes from this compound. Winemakers rely on it too, using it to adjust acidity for a sharper, cleaner taste and to help wine keep its color.

I remember seeing it on the ingredient list of effervescent aspirin tablets at the pharmacy. L(+)-Tartaric Acid works with sodium bicarbonate to create a fizz, making medicine easier to swallow. Manufacturers also use it to stabilize drug formulas, keeping them from breaking down on the shelf. It might even help certain medications dissolve faster in the body, a small detail with big effects for someone who needs quick relief.

Tartaric acid often acts as a base for salts that bind minerals like magnesium and potassium in tablet form. This helps nutrients break down more smoothly in the stomach, which is something nutraceutical companies count on for reliable products. Quality matters a lot here — both for regulatory reasons and for people’s health.

It surprised me how broad its uses run. Textile workers lean on tartaric acid during fabric dyeing, making colors richer and more stable. Construction crews mix it into cement as a retarder, slowing down the hardening process in hot weather. Even photographers from years ago used it in developing solutions, though that’s faded with digital cameras.

L(+)-Tartaric Acid rates as generally safe. It gets made in part from the waste of grape juice making, so it fits well in a move toward more sustainable sourcing. Still, questions keep cropping up about the long run. Oversight by food authorities anchors confidence in its safety, but transparency on processing methods matters. Watching for allergic reactions or misuse stays important, especially in products for children.

We need to keep looking for ways to lessen the environmental load. Finding sources with a smaller carbon footprint, or tweaking the process to cut waste further, feels smart to me. Companies that fill labels with clear, honest information earn more trust — and that ends up helping both consumers and producers.

L(+)-Tartaric Acid threads itself through more parts of life than most realize. Knowing its uses lifts some of the mystery from how everyday products work, and opens space to ask tougher questions about quality and safety in what we eat, drink, and use.

L(+)-Tartaric acid sounds exotic, but most people have eaten it without knowing. It shows up in many foods and drinks, especially wine and grape-based treats. It’s the stuff behind some of that tangy bite in candy and fizzy drinks, too. This compound comes from natural sources — mainly grapes — and also gets produced in a lab for food use. For decades, the food industry has counted on it to boost flavor, balance acidity, and even act as a stabilizer for baking powder.

A lot of additives in the food world raise eyebrows, and rightly so. Looking at L(+)-tartaric acid, safety records paint a reassuring picture. Tap into regulatory decisions from groups like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), and both put tartaric acid on their lists as safe for regular food use. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives reviewed it, too, setting no strict upper intake limit. That usually means low risk at amounts used in food.

Walk through a grocery store, and you'll find it in baked goods, jellies, jams, and soft drinks. Regular food is not meant to flood a person with high levels. If someone consumed massive doses all at once, they risk stomach pain or diarrhea, but such a scenario is rare. At typical levels seen in daily life, problems rarely surface. Even folks with sensitive stomachs rarely report clear reactions to tartaric acid.

Personal experience matters. Spend any time making homemade candies or baked goods and you may reach for tartaric acid to bring the right sour note or to help stabilize egg whites. Chefs rely on its unique properties to achieve flavors and textures people recognize and enjoy. Wine drinkers owe much of a crisp glass’s appeal to this very compound, whose natural presence in grapes shapes a drink’s final character.

Tartaric acid helps preserve some foods and increases the shelf life of items sensitive to spoiling. In the kitchen, it keeps colors fresh in boiled vegetables. In icing and meringue, it helps with structure and shine. Over centuries, people have built relationships with ingredients that work, and L(+)-tartaric acid is a quiet part of that story.

Scientific research remains a cornerstone to trust in food safety. Doctors and food scientists have looked at tartaric acid’s effects for decades. A few animal studies show that extremely high doses, possible only in a lab setting, can cause digestive problems but not long-term harm. Humans do not typically approach these levels through normal eating. Research published in public health journals and toxicology reviews echoes the view that this acid is well-tolerated.

No ingredient is beyond scrutiny. Sensitive groups — such as kids or those with allergies — deserve to know what’s in their food. Yet tartaric acid stands out for its long history and consistent safety record. People trust those clingy wine crystals on the bottom of old bottles because they spell tradition, not danger.

Food makers depend on regulatory oversight, so clear standards and honest labeling help people avoid surprises. It pays to keep up with trusted sources like the FDA, EFSA, and the World Health Organization for any shifts in the science. That said, for someone who sticks to standard servings and avoids wild experiments, L(+)-tartaric acid won’t pose a risk. Home cooks get to enjoy the results without worry as long as instructions are followed.

If manufacturers keep to established guidelines and buyers pay attention to how much tartaric acid they consume, health impacts stay off the radar. Outright avoidance is not necessary — just the common sense that keeps any ingredient in check.

L(+)-Tartaric acid might look like simple white crystals, but those crystals carry a lot of responsibility—showing up everywhere from wine barrels to pharmaceutical labs. Once I had a batch stored in a cluttered supply room with cracked windows, and it didn’t end well. Broken seals and humidity turned a perfectly clean product clumpy. This loss taught me a truth that every chemist and food producer knows: even something as basic as tartaric acid will lose its punch if handled carelessly.

L(+)-Tartaric acid thrives in dry, cool environments. Moisture can sneak in and create problems, turning it sticky or causing it to clump. Heat speeds up degradation, so avoid warehouses or rooms near machinery or sunlight. From a supplier’s view, temperature-controlled spaces keep quality high and waste low. Even a small increase in humidity and warmth can shorten the shelf life, leading to product recalls or wasted batches. Factory audits reveal that humidity above 60% and temperatures above 30°C give the wrong invitation to spoilage.

Choosing the right container saves a lot of headaches down the line. Sealed, airtight containers—glass or certain plastics—do the trick. Metal drums should stay lined or coated. In one dry goods facility, staff used unlined tins, which led to taint and eventually rusted through. Keeping tartaric acid in proper containers blocks out humid air and contaminants that shorten usability and affect safety. Regular checks for worn labels or seals stop mistakes before they start. I’ve seen entire shipments downgraded because a single loose cap let in moisture over time, damaging what could have been reliable supplies.

L(+)-Tartaric acid doesn’t threaten seasoned workers, but a little care goes a long way. Gloves and goggles keep dust out of eyes and away from skin. Clean scoopers and dry tools stop cross-contamination—a crucial detail in food or pharma plants. Regularly training staff to notice discoloration, caking, or funky odors prevents compromised batches from reaching consumers. Some companies flag products past their intended shelf life to avoid lawsuits or recalls. My own years in quality control taught me that even one overlooked step in storage can ruin consistency across production lines.

Damp basements, sudden power loss, or crowded storage racks threaten tartaric acid quality far more often than folks admit. Simple fixes work best: detailed logs, frequent inspections during humid months, and backup generators for climate control systems. Warehouses install cheap hygrometers and thermometers near their storage shelves and run drills for staff to spot and report leaks or spikes in temperature. Periodic cleaning and rotating supply bins reduce stale inventory and contamination. Even with the rise of automation, a sharp-eyed worker usually catches an emerging problem first.

Reliable storage means more than holding onto product for the long haul. It’s about trust—ensuring suppliers, manufacturers, and customers get what they expect every time. L(+)-Tartaric acid plays too big a role to risk slack habits. From small craft breweries to major pharma labs, attention to storage details shapes product performance and business reputation. Decades of hands-on work have shown that investing in careful handling pays off again and again, far more than any insurance payout or discount for spoiled inventory.

Taking care of any material starts with knowing how long it lasts. Walk into a food lab, a winemaking cellar, or even a school classroom, and odds are, you’ve seen that familiar, fine, white powder—L(+)-tartaric acid. It preserves, gives tang, adjusts pH, even separates crystal-clear wines from cloudy ones. But even the most reliable ingredients have a ticking clock. Shelf life turns from trivia into necessity once you rely on it for food safety, lab accuracy, or just holding value in inventory.

This acid comes in with a strong record. In my years dealing with food ingredients, I noticed how careful storage made some products last and last, while other batches spoiled because someone ignored the basics. With L(+)-tartaric acid, its shelf life usually stretches from three to five years. Yet, real longevity depends on how it’s kept: keep that bag sealed tight, away from moisture, sunlight, and heat. If it picks up just a bit of water from the air, it may start clumping, degrade faster, and stop working as intended.

The natural resilience of L(+)-tartaric acid comes from its crystalline structure. Left unopened, in its original packaging, it resists breakdown. But even a short exposure to humidity can start to ruin batches. Beyond just turning lumpy, contaminated acid can encourage mold growth—a safety risk most don’t expect from something so sharp and sour.

Not every kitchen or lab keeps a stock ledger with expiration dates. I’ve seen old supplies get used in small-batch wineries, even in classrooms, without a second thought. That shortcut runs real risks. Degraded tartaric acid doesn’t regulate pH properly. In food, this can open the door to spoilage bacteria or simply change the flavor profile beyond recognition.

Food safety agencies, including the FDA and EU regulators, back up strict timelines. Their standard advice pushes for using it within three years if opened or unused. Past that point, quality tests become necessary: taste, pH buffer testing, and clumping checks help make sure what looks fine still performs.

Extending shelf life isn’t magic—it takes discipline. Store L(+)-tartaric acid in tightly sealed containers, kept in cool, dry, and dark spaces. Once the main package opens, split it into smaller airtight jars for daily use. In bigger operations, regular testing to confirm purity and power pays for itself by cutting losses down the line.

For businesses, keeping accurate records makes a difference. Note the lot numbers, manufacturing dates, and test results. Audit old supplies once a year. Don’t be afraid to discard old, unused acid to avoid bigger problems down the road. Lab results can spot issues before they hit production, sparing headaches and costly recalls.

True reliability—whether in a vineyard, a factory, or a home kitchen—depends on respect for chemistry and care in storage. Companies increasingly lean into batch tracking and smart packaging that blocks out moisture and light, which helps keep shelf life predictable. For everyday users, the lesson sticks: treat this acid with respect and it’ll keep doing its job for years. Ignore the basics, and risk both outcomes and safety.

Shelf life for L(+)-tartaric acid isn’t about following rules for the sake of it—it comes straight down to safe, consistent results. In my own work and kitchen experience, a little extra care always pays off, especially where even small amounts of moisture or sunlight can cut shelf life short.

Supermarkets and kitchens carry plenty of products featuring tartaric acid, especially the L(+)-type. It comes from natural sources like grapes and tamarinds. Bakers recognize it as cream of tartar, giving structure to meringues and stabilizing whipped cream. Anyone who’s whipped up a cake or browsed ingredient lists in soft drinks and candies has probably crossed paths with it.

Food labels can look like puzzles for folks with allergies. Mystery names and long chemical terms leave people guessing. Is L(+)-tartaric acid risky for people with allergies? This is about safety on a daily level, for parents packing school lunches or bartenders mixing drinks.

True food allergens set off immune system alarms. These usually involve proteins, which cause reactions ranging from mild rashes to severe anaphylaxis. L(+)-tartaric acid comes from plants but isn’t a protein. Research, including reviews by food safety authorities in Europe and North America, shows no established connection between this acid and common food allergies.

One detail worth attention — L(+)-tartaric acid sometimes comes from wine production. Wine can involve other allergens like sulfites, but the acid itself does not belong to the same group. The FDA and EFSA list it among additives with an extremely low risk of allergic reactions. Neither organization includes tartaric acid among the “Big Eight” allergens (milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, fish, shellfish, soy, wheat).

People with celiac disease or food intolerances also face confusion around acids and other additives. Gluten cross-contact grabs headlines, but reputable tartaric acid sources avoid grain-based raw materials. Plant-based fermentation and strict isolation from cross-contaminants usually keep tartaric acid free from gluten, dairy, or nut traces.

Manufacturers who keep up with best practices run careful batch tests, publish specifications, and allow customers to see allergen statements. Always look for companies that answer questions directly, whether in a bakery or at a large food processing plant. Transparency serves everyone — customers, health professionals, and companies alike.

Allergy is different from intolerance or sensitivity. A handful of case reports describe mild stomach issues or mouth tingling after consuming products with tartaric acid. Sometimes this is due to the acid’s tart flavor, not a true immune response. If symptoms pop up, talk to a doctor and check the ingredient label for other suspects.

Many processed foods contain more than just tartaric acid. Look at the full package; gums, artificial colors, or preservatives often trigger adverse effects. If a company sources the acid from grapes and someone has a grape allergy, trace residues from fruit proteins could, in theory, show up. Verified allergen testing minimizes these risks.

No food additive works for every diet. People with allergies or sensitivities know to read labels and ask questions. Whether you cook for a crowded school cafeteria or craft small-batch sweets, the best approach is direct: pick trusted suppliers, demand full labels, talk to a health professional, and keep tabs on any symptoms. Nothing beats real-world awareness and open communication for keeping everyone safe.