Ferrous gluconate started making waves in the 19th century, at a time when scientists grew more interested in how to tackle iron-deficiency anemia. Before anyone thought about vitamin-fortified cereals or international guidelines for nutrition, the world used simple mineral salts to remedy iron shortage. Ferrous gluconate, sourced from gluconic acid fermentation and simple iron salts, filled a gap between raw iron supplements and products with improved absorption and taste. By the early 20th century, a growing understanding of chemistry spurred both pharmaceutical and food industries to use gluconates for their lighter taste and gentler effects on the stomach. Ferrous gluconate became a more familiar ingredient in over-the-counter iron tablets, and it still holds a spot among standard iron supplements worldwide.

Ferrous gluconate mostly shows up as a yellowish-gray or light greenish powder. It’s water soluble and leaves very little taste, compared to other iron sources. You find it in multivitamins, baby formulas, fortified foods, and medicines. Some canned foods—like olives—turn to ferrous gluconate for more than its nutritional value. It helps preserve color and keeps food from turning an unappetizing brown. Some large supplement brands trust ferrous gluconate to deliver steady iron content and fewer digestive issues than harsher iron salts, like ferrous sulfate.

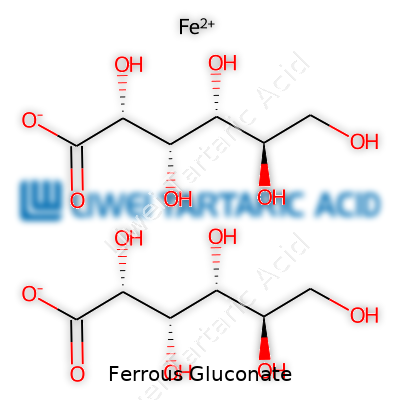

As a chemical, ferrous gluconate carries the formula C12H22FeO14·2H2O. On the shelf, it stays stable if kept dry and away from heat. It starts to degrade with excess moisture or strong sunlight. With a molecular weight of about 482 grams per mole, it ranks among iron supplements with higher solubility, making it easier for the body to absorb the iron. The fine powder feels light and doesn’t clump much, which simplifies the manufacturing process for tablets and other solid forms.

People working in the supplement industry need to follow strict quality benchmarks for ferrous gluconate. Reputable products list the percentage of iron—usually near 12% by weight—in compliance with pharmacopeial standards like the USP or EP. Good labels break down mineral content, any additives, and batch information for traceability. For food use, countries such as the US and those in the EU require clear labeling, so at-risk populations—pregnant women, children, anemic patients—aren’t left in the dark about dosage and potential side effects.

A common manufacturing process starts with mixing gluconic acid or its salts (from corn or beet sugar fermentation) with ferrous carbonate or ferrous hydroxide. The blend reacts at a gentle temperature in water, forming ferrous gluconate crystals. The solution is filtered, concentrated by evaporation, then dried through careful heat application. The result—crystalline ferrous gluconate—is run through sieves, cooled, and milled to the desired size. Labs run quality tests for purity, iron content, moisture, and contaminants at each step.

Ferrous gluconate can oxidize to ferric compounds in the presence of air or excess water, reducing its value as an iron supplement. To prevent this, manufacturers sometimes add antioxidants or package the product with desiccants. In food processing, the mild reducing quality of ferrous gluconate prevents the browning of canned vegetables and fruits. Chemical reactions with acids or bases can split the gluconate apart, so producers store it in pH-neutral conditions. Several experiments tested modified ferrous gluconate—by chelating it with other organic acids or encapsulating it for slower release in the digestive tract—to improve absorption or masking any iron aftertaste.

Pharmacies, food factories, and chemical suppliers use several names for this compound: iron(II) gluconate, E579 (in food ingredients lists), and ferroglyconate. On some medical products, you’ll see “Ferrous Gluconate Tablets” or “Iron Gluconate Oral Solution.” Multilingual labeling always mentions its iron(II) salt status, distinguishing it from ferric forms used less often for supplementation.

Ferrous gluconate brings a solid safety record when users stick to recommended doses. Regulatory agencies—including the FDA and EFSA—review data on daily intake limits, nutrient content claims, and risk of overdose. Facilities handling the bulk chemical use dust control and employee training to minimize inhalation or accidental exposure. Product recalls nearly always come from labeling errors or foreign material contamination, not toxicity from the gluconate itself. Many workers in the sector remember cases of severe iron poisoning, mostly tied to accidental ingestion of high-dose supplements by young children. Those cases push companies to make safer packaging and clearer warnings for iron-containing products.

Ferrous gluconate’s reach goes beyond pharmaceutical bottles. Grocery store shelves feature baby cereals and nutrition bars fortified with this compound to address iron gaps in kids’ diets. Hospitals and clinics rely on it for patients with iron deficiency but who struggle with side effects from stronger iron salts. Olive packers, in southern Europe and the US alike, include it in their brining tanks to keep black olives glossy and dark for months on end. Animal feed producers often select this gluconate for fortifying pet foods and livestock diets, searching for both nutrition and stable shelf life.

Over the past decade, R&D groups have champed at the bit to improve how the body processes iron from oral supplements. Research teams tackle issues like absorption in patients with chronic illnesses or in children who have trouble processing regular iron. Bioavailability studies compare ferrous gluconate with other complexes—like ferrous bisglycinate and ferric polymaltose—across gut health, food interactions, and symptom relief. Some teams investigate nanoparticles or new carriers, hoping to solve stubborn issues with poor tolerance or low uptake in special patient groups. Few pharmaceutical ingredients match the research pipeline of iron compounds, thanks to the scale of global anemia and the knock-on effects on children’s cognitive development and maternal health.

Ferrous gluconate runs a low risk of toxicity at regular nutritional doses. Human studies link overdose to gastrointestinal upset—nausea, cramps, diarrhea—but not to severe organ damage at recommended dietary levels. High ingestion, especially by unsupervised children, can still trigger acute iron poisoning. Hospitals treat such emergencies with chelating drugs and gastric lavage. Surveys among poison control centers consistently call out accidental overdoses, often from bottles not secured away from young hands. Researchers continue looking for better taste-masking and childproofing measures to shrink the number of dangerous accidents.

Ferrous gluconate holds a steady future in sectors—from healthcare to food processing—seeking reliable iron without harsh side effects. As food science pushes the boundaries of fortification strategies, this compound promises gentler options for at-risk groups in developing regions. New research heads toward synergies with prebiotics or anti-inflammatory agents to boost absorption and stomach tolerance. Advances in microencapsulation may soon deliver slower-release iron that fits the needs of special diets. More change is on the horizon, but the track record of ferrous gluconate signals staying power, as it adapts to next-generation food and pharmaceutical trends while watchdogs keep a close eye on its safety and impact.

Doctors see folks walk into their offices tired, pale, sometimes short of breath. Iron deficiency turns up way more often than most expect, especially among kids, pregnant women, and older adults. Ferrous gluconate steps in as an iron supplement that’s been around for ages, usually to help people fight off iron deficiency anemia. It delivers iron—an absolute must for building up healthy red blood cells—without hitting as hard on the stomach as some older iron salts do. I’ve seen friends struggle with other iron pills, complaining about stomach cramps or feeling nauseated. Ferrous gluconate, on the other hand, tends to be gentler for those with touchy stomachs.

Feeling wiped out isn’t just about energy. Low iron means blood isn’t carrying enough oxygen around, so just walking to the mailbox gets tough. Kids don’t grow like they should. Adults miss work or school. Iron deficiency affects thinking skills, even mood. It’s easy to think a simple pill does the trick, but the science backs up the need for iron. According to the World Health Organization, anemia from iron deficiency impacts more than 1.6 billion people. Women of childbearing age run the highest risk, thanks to monthly blood loss and pregnancy demands.

Not everyone who’s low on energy needs ferrous gluconate. Sometimes a meal rich in leafy greens, beans, or red meat can help bring iron levels back up. But for people who struggle to get enough from food—like strict vegetarians, pregnant women, or those with gut conditions—supplementation turns from “nice to have” into “must-have.” Ferrous gluconate shows up in multivitamin bottles, stands alone in iron pills at pharmacies, and even gets added to foods like breakfast cereal or baby formula. It’s especially handy for people who just can’t tolerate ferrous sulfate, its rougher cousin.

Ferrous gluconate has iron in the “ferrous” form, which the intestines absorb much more easily than the “ferric” form. Some studies showed that this version of iron upsets the stomach less than iron sulfate—fewer cases of constipation or upset stomach. This makes it a common first choice in clinics. A standard 240 mg tablet delivers about 27 to 30 mg of elemental iron, enough to chip away at mild to moderate anemia without overdoing it.

Doctors ask for regular blood tests to track iron status and ferritin. Taking iron pills with vitamin C helps the body soak up more iron, so a glass of orange juice alongside makes sense. Dairy, coffee, or antacids, on the other hand, can slow down absorption. While self-diagnosing and grabbing any old supplement off the shelf won’t solve deeper health issues, ferrous gluconate does offer a trustworthy solution for those needing real help to build their iron stores again.

Too much iron causes problems. Poisoning can land a child in the hospital quickly, so parents keep these pills tucked out of reach. Grownups notice that black stools or tummy pain often signals either too much or not quite the right fit. Talking with a doctor before starting ferrous gluconate makes sense and helps avoid trouble. Iron works best when it’s matched to the actual need, not just symptoms read off a list. For those who struggle with chronic shortage, these small tablets fit the bill—and help people get back to daily life without that drag that low iron brings.

Fatigue started creeping into my days several years ago. After my doctor ran some tests, it turned out that low iron was dragging me down. Ferrous gluconate entered my life soon after that. This supplement, basically a form of iron, gives your body a chance to rebound when food alone isn’t cutting it. Iron carries oxygen through the blood, and without enough, simple chores feel tougher than they should.

Everyone’s body reacts a little differently to iron supplements. Your healthcare provider will usually recommend a specific dose based on your blood work. I stuck with mine’s advice, and it helped steady my iron levels much faster than if I’d guessed at my own dose. For many, it’s one tablet daily, but people with especially low iron may need higher amounts. Too much iron can harm your organs, so I never tried to “speed up” recovery by doubling up on pills.

My pharmacist told me to take ferrous gluconate on an empty stomach, with a glass of water. That helps your body soak up more iron from each tablet. Sometimes, though, the stomach disagrees. I learned pretty quickly that taking it after a light meal—think toast or cereal—kept the queasiness away. Some foods, especially dairy and whole grains, can block iron absorption, so I planned my snacks to avoid mixing them too closely with my pill.

I tried multivitamins with my iron pills at first, thinking the more nutrients the better. Turns out, calcium and antacids can slow iron’s journey into your bloodstream. I started taking any other supplements at a separate time of day, and that made a difference in how I felt. On the flip side, taking vitamin C—a glass of orange juice, for example—does help your body take in more iron from each dose.

Ferrous gluconate can mess with your digestion. Constipation is a real struggle for some people, and I felt it in the early weeks even with plenty of water and fiber. Dark stools aren’t anything to worry about—that’s just a sign the iron is in your system. Gut discomfort shows up for some more than others. I brought this up to my doctor, who tweaked my dosage and gave me tips for managing the side effects. No one should feel like they need to brave side effects in silence.

Taking iron every day can feel like a chore, but setting a routine helps. I kept my bottle on the kitchen counter as a daily reminder. Tracking progress with blood tests also kept me motivated—iron levels take time to rise, and patience pays off. Sharing my experience with friends made it easier to remember that lots of others deal with low iron, too.

Some effects of too much iron can be serious—nausea, stomach pain, or unusual tiredness—even if they sneak up slowly. Checking in with a doctor every few months kept me safe and on the right path. Open conversations about supplements, side effects, and your regular diet mean fewer surprises and better health. Iron is just one piece of the puzzle; it takes some trial and error to figure out the rest.

Most folks look for something simple to beat iron deficiency, and ferrous gluconate pops up in that search more often than not. I remember sitting in a doctor’s office, clutching a prescription for iron tablets, not really thinking much about the side effects. I soon learned why the pharmacist handed me that warning pamphlet. Digging into those reactions can help others know what’s coming, and maybe even dodge some trouble.

Many people swallowing down their daily dose meet stomach issues first. Stomach pain, constipation, or diarrhea are the most common complaints. Once, at a family barbecue, my cousin talked about her struggle with abdominal cramps after starting ferrous gluconate. She thought something she ate triggered it, but it turned out to be the iron.

Nausea hits a lot of people too, especially if they take the tablet without food. Some just push through, thinking it’s the price they have to pay for better health. I tried taking the tablets on an empty stomach as suggested by some advice, but lunch soon became my new pill-taking companion to ease that sick feeling.

One side effect no one warns about: black stools. It's not usually something to worry about since it signals your body dealing with extra iron. Many people mistake this for blood in their stool, which can be scary. Still, any dark red or tarry stools should be checked out because it could point to something more serious.

Allergic reactions don’t turn up that often, but they do happen. Signs like rash, swelling, or trouble breathing call for a trip to the doctor, fast. I’ve never had this issue myself, but reading about cases in clinical reports reminds me not everyone reacts the same way.

There’s another risk that deserves some spotlight: iron overload. People with certain genetic traits, like hereditary hemochromatosis, risk storing too much iron, even from regular doses. Too much iron can hurt organs over time—something most doctors catch early with regular blood tests, but not everyone gets checked before reaching for a supplement.

Managing these side effects isn’t always straightforward. Healthcare providers recommend eating more fiber or drinking plenty of water for constipation. In practice, adding fruit and whole grains helped me more than any stool softener. Folks can also talk to their doctors about switching to a different iron compound or cutting back the dose temporarily if side effects get harsh.

Choosing to stay with ferrous gluconate or trying something else comes down to honest conversations during checkups. Making sure to review medications, underlying conditions, and even diet can spare people a lot of discomfort.

It pays to get regular blood tests while on iron supplements. People who don’t need iron shouldn't take it just “in case.” I learned to avoid taking my iron pill with coffee or tea, since these drinks cut down the body’s iron uptake. Squeezing some orange juice next to the pill worked better for me, and the science backs that up—vitamin C really helps.

Listening to your own body when starting any supplement leads to fewer surprises. Most importantly, a real discussion with the doctor can prevent anyone from making the same uncomfortable mistakes I made.

Pregnancy flips your world upside down. Your appetite shifts, your body changes shape, and your doctor starts using words like “hemoglobin” and “anemia.” Iron takes center stage here, because you’re not just eating for two in calorie terms—your blood volume climbs, and iron keeps both you and your baby supplied with healthy oxygen. I sat in my obstetrician's office, hearing those numbers, and started to pay real attention to my nutrition in a way I hadn't before. Iron deficiency got real for me. I remember how exhausted I felt before getting my levels up; it’s not a tiredness you just shake off.

Ferrous gluconate comes up a lot in prenatal conversations. It’s one of several forms of supplemental iron, along with ferrous sulfate and ferrous fumarate. The body absorbs ferrous gluconate pretty well, and many find it easier on the stomach than other forms. Less stomach upset means sticking to the doctor's plan is a bit less of a chore. After meals, a glass of orange juice helped tamp down nausea and boosted absorption with vitamin C.

Supplement shelves can be downright overwhelming, and the one-size-fits-all advice doesn’t really cut it here. Doctors run iron panels because too little iron puts mom and baby at risk, but piling on too much isn’t good either. High iron doses can cause problems like constipation, stomach pain, and in rare cases, risk poisoning. Pregnant folks need about 27 milligrams of iron per day, as set by the National Institutes of Health. Prenatal vitamins cover some of this, but iron levels differ between products, so checking with your healthcare provider makes all the difference.

Online forums dish out plenty of advice—some helpful, some way off the mark. I saw posts swearing by this supplement or that one, or suggesting wild home remedies. Evidence-based recommendations always come out ahead. Harvard Medical School, Mayo Clinic, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists offer straightforward, science-backed guidance: use iron under the guidance of a healthcare professional.

The day I picked up my prescription, a nurse gave me the talk: take it with food if my stomach protested, avoid milk and coffee close to pill time because they block absorption, and remember vitamin C helps iron soak in. I learned not everyone tolerates every brand or formulation, so staying honest about side effects allowed the team to tweak my plan. Some doctors recommend slow-release versions or even liquid iron for tough cases.

Struggling with side effects or uncertainty about dosing? Open communication with a doctor or midwife helps create a plan that fits real life. If constipation hits, fiber-rich foods and plenty of water help. Doctors sometimes stagger doses or use alternate-day regimens to lower discomfort.

Ferrous gluconate serves a purpose for many pregnant people who need supplemental iron. Trusting medical advice over hearsay and checking labels for actual iron content protects everyone involved. This isn’t just about following a trend—it’s about protecting one of the most important stages of life, for both parents and babies.

Taking an iron supplement like ferrous gluconate looks simple enough—a pill here and there to bring up your iron levels. Hidden beneath that routine, though, some real headaches can pop up when this supplement gets mixed with prescriptions or over-the-counter tablets. Not every doctor, pharmacist, or website makes this point clear. But from years of working with folks who take all sorts of medications, I’ve seen forgotten conversations about drug interactions come back to bite people. These issues aren’t stuffy academic warnings—they show up in clinics—and they remind us to get curious about what’s sharing space in our medicine cabinets.

Acid reducers or basic antacids—think Tums, Rolaids, Prevacid, omeprazole, or Pepcid—are likely the most common problem partners for ferrous gluconate. Iron needs stomach acid for comfortable absorption. Antacids lower that acid, and suddenly, your body pulls far less iron from the supplement. I saw a lot of older adults who religiously took heartburn medications, yet struggled to raise their iron counts, even on high doses of iron.

For people tackling both low iron and stomach troubles, it helps to separate taking ferrous gluconate and antacids by at least a couple hours. Swallow the iron with orange juice or vitamin C to boost absorption, which really can make a difference.

A lot of antibiotics, especially tetracyclines (like doxycycline) and some quinolones (such as ciprofloxacin), latch onto iron and form a complex that the body doesn’t absorb well. The end result—neither the antibiotic nor the iron work as intended. A tough infection sticks around longer, and iron levels don’t budge. I’ve seen this in younger folks treated for acne, where they end up with both stubborn skin issues and low energy because their iron replacement fails.

Spacing out these meds makes a major difference. Aim for a minimum gap of two hours before or after taking iron when using these antibiotics.

Levothyroxine, a common thyroid medication, has its absorption cut in half by iron supplements. For those managing thyroid disease, that spells weeks of fatigue or unexplained symptoms until someone pieces together the timeline. Even certain meds for Parkinson’s (like levodopa), and for bone health (bisphosphonates) struggle when taken close to iron.

Some vitamins and minerals mingle with iron in unexpected ways. Calcium, usually in dairy or supplements, hogs the same absorption route and winds up beating iron to the punch. Even zinc and magnesium taken at the same time can nudge iron out of the way. In busy families, I saw parents toss all vitamins into a daily pill box, hoping to build health, not realizing some nutrients compete against each other.

Ignoring drug interactions leads to wasted effort, persistent symptoms, and extra bills. No one wants surprises like persistent anemia, tiredness, or trouble managing other chronic conditions. Ask pharmacists to double-check your list. Keep a written log of all supplements and share it with each provider. Bring supplements, prescriptions, and over-the-counter bottles to appointments.

Iron matters. Using it wisely, in the right order, brings better health with fewer rough weeks guessing why nothing is working. Proper timing and a little knowledge go a long way—so your energy returns and you avoid the pitfalls that can hide in a daily pill routine.