People have used copper compounds for centuries. The Egyptians colored their cosmetics with copper-based pigments. In medicine, folks turned to copper centuries ago for its supposed healing properties, long before the lab work backed any claims. The story moves forward as the 20th century ushered in food science and pharmaceutical chemistry. Copper gluconate came into play because scientists wanted a way to deliver copper that the body actually absorbs. Regular copper salts sometimes just pass straight through. Gluconic acid, already a mainstay from fermentation, gave a ticket to better solubility. This pairing of copper with gluconic acid produced a supplement that could work without turning food or tablets into a chemical soup. Supplement makers and food industries took note. Today, copper gluconate appears everywhere from multivitamins to fortified drinks. It bridges ancient curiosity and modern regulatory standards—someone looking to boost copper intake can trust it has gone through rigorous development.

Copper gluconate isn’t flashy. It shows up as a pale blue or blue-green powder, mixing well into liquids and blends with other nutrients. Most folks run across it in the ingredient list of a supplement bottle or on the back of an energy drink can. With its easy dissolving nature, food producers sprinkle it into baked goods or beverages without fuss. Pharmaceutical players lean on copper gluconate because its bioavailability means the body gets a fair shot at absorbing this trace mineral, which plays a big role in helping enzymes do their job. A nutritionist might see it as an insurance policy against copper deficiency, especially in people with problems absorbing minerals.

Looking at copper gluconate, the color stands out—a blue-green that gives away the copper content. The powder absorbs water from air, not enough to clump but enough to matter in how it’s handled. Copper gluconate dissolves readily in water; put it in a glass, stir, and the powder vanishes. Taste-wise, it leaves a faint metallic impression—something you’d rather cover up in a sports drink or chewable vitamin. Compared to many other copper salts, its solubility and lack of bitterness make it suitable for food and medicine. The compound’s stability allows it to survive harsh tableting machines or thermal processing.

Product specifications tell the story of quality and safety. Whether from a supplement producer or food factory, copper gluconate needs clear labeling: total copper content, purity of the lot, moisture level, and absence of heavy metals like lead or cadmium. The U.S. Pharmacopeia and European standards spell out exact percentages, typically copper content falls right around 12%. Traceable lot numbers provide accountability. Labels in grocery aisle supplements highlight exact copper amounts, source, country of origin, and recommended daily values. Regulations make sure every microgram listed meets the lab tests and doesn’t ride in with unhealthy impurities.

Manufacturers usually synthesize copper gluconate by reacting gluconic acid with copper carbonate or copper oxide. This isn’t like mixing sugar for coffee; it needs careful control, a tank of pure gluconic acid, and copper source dumped at a slow rate. Temperature matters, otherwise copper salts might fall out as sludge, not powder. Suppliers run reactions until everything dissolves. Neutralizing the solution keeps the chemistry in line, after which filtration and drying take over. The end result: free-flowing powder, ready for packaging after passing battery after battery of purity checks. Each batch has records covering the journey from base chemicals to finished supplement.

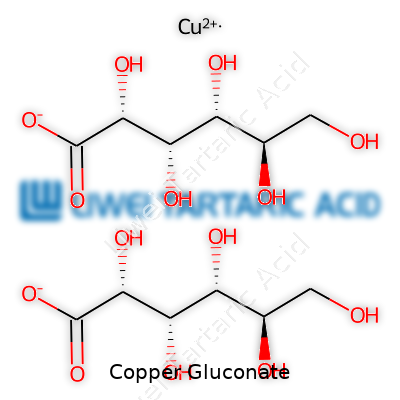

Copper gluconate results from a straightforward acid-base reaction—copper carbonate bubbles in gluconic acid, creating copper gluconate, water, and carbon dioxide. This process can tweak the solid’s physical traits. Some factories substitute copper oxide, getting the same result with just a different byproduct. Technologists have worked on ways to adjust particle size, avoiding chunks in finished products. They also account for the possibility of small copper oxide or hydroxide leftovers, which need clarification or further processing. All modifications must maintain the copper as copper(II), since copper(I) simply doesn’t play the same nutritional role.

Copper gluconate goes by several names. Chemical suppliers may call it cupric gluconate or simply E578 when added to foods. Some product sheets use copper(II) gluconate. Across supplements and food, these names refer to the exact same compound—different routes to the same trace nutrient. Finished products range from tablets to liquid tonics; sometimes the name rides the smaller print, outshone by flashier branding. In regulatory circles, E578 acts as shorthand, recognized on ingredient panels across the world.

Safety comes first in every production batch. Facilities working with copper gluconate enforce strict cleanliness, trace metal monitoring, and staff training to avoid cross-contamination. Operators use gloves and dust masks. Air filters pull fine powder from rooms, keeping exposure levels within the tight bounds set by workplace safety agencies. Food-grade suppliers submit each lot to microbial and heavy metals testing. Safety data sheets label copper gluconate as low-hazard, though handling large quantities without protection risks eye or skin irritation. Manufacturers keep records showing compliance—no corners get cut, since any shortcut risks a failed compliance audit or product recall.

Copper gluconate finds its way into a bunch of real-world uses. In supplement shops, it anchors the mineral complex tablets. Baby formulas and sports drinks use it to meet nutritional guidelines. Veterinarians sometimes prescribe feeds fortified with copper gluconate for animals showing deficiency. Skincare creators tout it for its role in collagen cross-linking and wound healing. Certain food products—especially meal replacements—lean on copper gluconate to round out their mineral claim. Even water purification companies test copper gluconate as a way to inhibit biofilm or algae growth, given copper’s antimicrobial punch.

Universities and research labs continue to study copper’s behavior in the human body. Genomics and trace mineral research zero in on how efficiently copper gluconate gets absorbed compared to other copper forms. Recent years have seen more studies on copper’s effects in neurological health since certain enzymes in the brain depend on copper. Researchers are probing nano-modifications, bound copper forms, aiming for even finer absorption or slower release. Food scientists keep tweaking how copper gluconate holds up in high-heat or high-acid conditions to expand its use in processed foods and drinks. Each project helps regulators and the public know exactly what happens at each mg dose.

Copper gluconate is safe in the right quantities, but too much builds up and hurts the liver or kidneys. Medical journals chart cases of copper toxicity, usually involving industrial accidents, not responsible supplement use. Clinical trials work to establish clear tolerable upper intake levels. Scientists check how copper interacts with zinc and iron ingested from the diet, making sure supplements don’t tip balances in a harmful direction. Some animal studies have outlined the early warning signs—jaundice, stomach upset, and anemia—all rare in responsible human dosing. All findings point to one takeaway: stick to daily values, don’t experiment outside doctor advice.

Copper gluconate sits at the intersection of nutrition, chemistry, and public health. Nutritional science may uncover even more subtle roles for copper, forcing industry to adapt how it delivers this mineral. Companies might pivot to new delivery systems—microencapsulation for timed release, or blends that improve flavor. Some researchers suggest copper-based compounds as possible agents for managing metabolic issues or supporting immune response, particularly in older adults. Regulatory agencies are watching closely, updating rules in response to fresh toxicity findings or improved analytical tools. Future production processes may cut waste streams further or boost recovery of copper from recycling. Food fortification programs in developing countries could find copper gluconate a simple solution to widespread deficiency, especially as vitamin and mineral gaps come under sharper focus with global nutrition surveys.

Walk into any pharmacy and you’ll see shelves lined with supplements promising to boost wellbeing. Among the usual suspects like vitamin C and zinc, you might stumble across copper gluconate. It seems like a tiny detail on a nutrition label, but this trace mineral plays a role that’s hard to ignore. My own grandmother once insisted on a bottle after reading about “energy support” in her favorite health magazine. Turns out, she was curious for good reason.

Copper gluconate works as a source of copper, an essential mineral that most people don’t spend much time thinking about. Yet, copper is involved in keeping the immune system on its toes. It helps enzymes do their jobs—a bit like grease making sure gears turn smoothly. These enzymes help form red blood cells, which carry oxygen throughout the body. That’s enough to matter for someone who tires easily.

Some days, diets fall short. Coffee and toast at breakfast, a sandwich for lunch, and maybe takeout at dinner. Processed food rarely brings enough copper to the table. Dietitians point out that copper-rich foods like shellfish, nuts, and seeds can help, but not everyone includes these in daily meals. That’s where copper gluconate supplements slide in. They offer a once-a-day capsule that aims to top off what’s missing.

Not all copper supplements work the same. The gluconate form dissolves well in water, so it gets absorbed more smoothly when taken orally. I learned this one semester in college after struggling through reports about different mineral supplements. The gluconate form won out for ease and tolerability. The FDA recognizes copper gluconate for food fortification, which means it shows up in multivitamins, as well as certain fortified foods like breakfast cereals.

It’s easy to think if a little is good, a lot must be better. Copper doesn’t play by those rules. Too much copper in the system can cause stomach pains, nausea, or, over the long term, even liver damage. The National Institutes of Health sets the daily value for copper at 0.9 mg for adults and says to keep daily intake below 10 mg. Most copper gluconate tablets hit a dose that lands safely beneath these amounts. Anyone already getting enough copper in their diet won’t benefit from extra pills—and the risks aren’t worth ignoring.

Copper gluconate can fill gaps where diets miss, but there’s more to building good health than grabbing whatever supplement sounds helpful. Health care professionals point to a food-first approach, urging patients to check copper levels through regular nutrition panels, especially for people with absorption issues or those on restricted diets. I always appreciated the straightforward advice from my old dietitian: focus on variety on the plate before opening another bottle at the drugstore.

A bit more public awareness goes a long way. Instead of relying only on online ads or word-of-mouth, people deserve practical information about real risks and benefits. Copper gluconate serves as a reminder that every nutrient is part of a bigger picture—not a solo act, but an ingredient in a much larger recipe for health.

Copper plays a key role in keeping the body healthy. It helps build red blood cells, supports immune function, and assists in energy production. My own curiosity about copper supplements started after a friend mentioned taking copper gluconate for fatigue and brittle hair. Like many others, she trusted a product because of an online review. But safety deserves a closer look.

Copper shows up everywhere: shellfish, nuts, dark chocolate, leafy greens. It isn’t hard for most people eating a varied diet to meet daily needs. Adults require only about 900 micrograms of copper each day, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Deficiency looks rare unless someone has a medical problem affecting absorption, such as Menkes disease or chronic digestive issues. Too little copper can cause anemia, low immunity, and weak bones.

Supplements change the game. Too much copper can turn toxic. Most copper supplements, including copper gluconate, deliver higher amounts than what food provides. According to NIH guidelines, daily copper intake should not exceed 10,000 micrograms for adults. Prolonged exposure to higher levels throws off zinc balance, causes nausea, abdominal pain, and can even harm the liver. Symptoms of copper overdose sometimes mirror copper deficiency, which can confuse matters further.

Many supplement makers use copper gluconate because it dissolves well and absorbs quickly. This doesn’t automatically translate to better safety or greater need. Just because a label says “gluconate,” it doesn’t make overdose less likely. The form of copper won’t change the risk of toxicity, only the amount does. Like me, many consumers forget to compare dietary sources with supplement dosage. A single tablet may contain ten to twenty times more copper than what’s found in a serving of beef liver.

Some people shouldn’t use copper supplements without careful guidance. Those with Wilson’s disease, for example, already have trouble eliminating copper. Adding more copper, even in supplement form, only worsens liver and neurological issues. Pregnant women usually meet their needs through prenatal vitamins. Children need much less copper than adults, so adult supplements could overwhelm young bodies. The elderly sometimes get copper from plumbing or cookware, not just diet—raising the risk for unintentional exposure.

Registered dietitians and doctors agree: blood tests offer a clear picture of copper status. Most folks have no trouble meeting copper needs through balanced meals. Diet trackers and apps make calculations easier now. Supplements may help people who have been diagnosed by a healthcare professional with a true deficiency. Without a lab result and a doctor’s advice, adding extra copper makes little sense.

Many products promise energy, immunity, and healthier skin with copper gluconate. Reality shows these claims only hold up in deficiency cases. Skipping over the risks and ignoring professional input leaves room for harm. A safer path starts in the kitchen: toast some pumpkin seeds or add lentils to soup. If a doctor spots a deficiency, they’ll explain exactly how much copper and what form works best.

Copper gluconate can play a role for people with a confirmed need. Unchecked and unsupervised, copper supplements threaten to tip the balance the wrong way. Conversations with healthcare providers, smart food choices, and a wary eye on labels ensure copper works for health, not against it.

Copper takes on a quiet but vital role in our lives. We rely on it for nerve health, energy, and keeping blood vessels in good shape. Packaged in capsules or added to fortified foods, copper gluconate keeps showing up on store shelves. On paper, it looks like a ticket to better nutrition, especially when many folks worry about not getting enough minerals. Real-life use, though, raises questions about what happens once that pill lands in the stomach.

Most folks who take copper gluconate do it to tackle a deficiency or get a wellness boost. Stomach pain, nausea, and diarrhea join the list of complaints. Friends of mine who tried it described the same cramps and queasiness you get when a supplement piles onto a sensitive gut. The stomach just seems to notice copper more than other minerals. A few hours after swallowing the dose, the payoff can feel rough enough to skip it next time. Clinical research backs up these concerns. One study points to copper’s effect on the GI tract, especially as doses climb. None of this comes as a shock to doctors who see patients with upset stomachs linked to multivitamins or separate copper products.

The body only needs a pinch of copper. Taking copper gluconate in high amounts can load extra work onto the liver. Years ago, my uncle tried boosting his mineral intake and soon wound up with fatigue and yellowed eyes—a classic sign of liver stress. Blood work later showed elevated liver enzymes, and doctors narrowed it down to months of enthusiastic supplement use. Scientists have known for decades that too much copper builds up in the liver and can damage its cells. Copper toxicity stays rare, but liver problems show up in medical textbooks and online forums from folks who go overboard.

Mood swings and brain fog sneak up for some who don’t realize copper can influence the mind. Anxiety, irritability, and trouble focusing have been reported by people using copper gluconate without realizing the impact on brain chemistry. Years ago, a nutritionist told me about a patient convinced she had early dementia, only to find copper supplement use behind her symptoms. The truth is, excess copper interferes with dopamine and other neurotransmitters. Studies from the National Institutes of Health mention this same pattern—too little or too much copper upsets balance, with possible effects on mood and cognition.

Most allergic reactions stay on the rare side, but they do happen. Red, itchy rashes or swelling showed up in a few case reports linked to copper gluconate supplements. Years of working in a pharmacy left me with stories of customers returning bottles, saying hives or mouth sores popped up soon after starting new vitamins. Researchers believe some additives or the copper itself might trigger responses in sensitive people. These issues typically clear up after stopping the supplement, but the experience rattles those who expect only benefits from a mineral.

There’s no shortcut to better health. Relying on real food—beans, nuts, whole grains—lets you get essential copper without rolling the dice on supplements. For those dealing with low copper diagnosed by a doctor, supplementing should come with regular blood checks and guidance from a healthcare provider. Reading ingredient labels and watching for side effects makes a difference. If new or troubling symptoms crop up, it pays to step back and talk with a medical professional before sticking with any over-the-counter solution.

Knowledge grows by listening to both science and personal stories. Paying attention to symptoms, respecting doses, and not self-diagnosing with supplements helps keep health on track. Copper gluconate can fill gaps for some, but the side effects remind us every shortcut comes with trade-offs.

Copper lives in food like whole grains, shellfish, seeds, and nuts. Plenty of folks get what they need straight from their plate, with the National Institutes of Health pointing to 900 micrograms of copper per day for adults as the sweet spot. Stepping into the world of supplements, copper gluconate usually sits at the low end of copper’s recommended daily limits. Each milligram of copper gluconate packs just a small fraction of pure copper—a detail easily overlooked on most supplement labels.

Standing in a pharmacy aisle or scrolling through an online catalog, doses hover around 2 mg of elemental copper per pill. That can look harmless, but taking more than what the body needs builds up trouble—especially with daily use. Zinc and iron, two heavy hitters in a regular diet, butt heads with copper absorption. Getting too much copper saps zinc levels, turning what starts as a boost into a health hazard.

Copper deficiency crops up rarely and usually in people with specific health concerns: folks with malabsorption, or on long-term tube feeds. The average diet rarely comes close to falling short. If you’re worried about your copper intake, a blood test tells the real story.

Science and government guidelines keep it simple: 900 micrograms per day on average, never blowing past 10 mg per day—the set tolerable upper intake level for adults. This number isn’t just a guess. Toxicity stories almost always involve doses that go beyond this mark, often through poorly monitored supplementation. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) tightly regulates supplement claims but leaves the door open for overuse if buyers skip medical advice.

Across the years, working with nutrition clients revealed a trend. Many chase after a single mineral, like copper, hoping for quick fixes—stronger hair, sharper minds, or that elusive extra energy. Balance trumps overcorrection every time, especially where trace minerals come into play.

Reading supplement bottles, folks rarely spot how different types of copper change what the body absorbs. Copper gluconate gets absorbed better than some versions, but that can mean even a small excess builds up quickly. Side effects show up fast: cramping, nausea, and even liver problems if the habit continues.

Doctors don’t throw around copper prescriptions for fun. If you’re short in copper, odds are higher you need to address another underlying health problem—not just pop a pill. Working in clinics, this came up time and again: correcting the bigger issue worked better than covering up symptoms.

Health isn’t one-size-fits-all, and supplement needs shift with age, diet, and medical history. It always pays off to bring a doctor or a registered dietitian into the conversation before reaching for copper gluconate. They dig into your health history and current diet, then help you land close to that 900-microgram target—no guesswork.

If supplements still feel like the solution, looking for third-party testing on the bottle helps weed out risky choices. An FDA warning letter or a sketchy website usually spells more harm than help. At the end of the day, nature wins—most people find enough copper in well-rounded meals, paired with real-life advice from a qualified professional.

Copper doesn’t get the same spotlight as iron or calcium, but it plays a key role in human health. Copper gluconate, a common supplement form, often appears on the ingredient lists of multivitamin bottles, energy drinks, and even lozenges for sore throats. Plenty of people assume extra copper just boosts health, but it’s not that simple—especially if someone takes prescription or over-the-counter medications.

Pharmacies keep running into questions about vitamin and mineral supplements—especially since people often forget to mention them during doctor visits. Copper’s a trace mineral, but the body has a narrow window for how much is safe. Certain drug combinations make that window even smaller.

Zinc and copper both rely on similar transport systems in the gut. Taking high-dose zinc supplements for long periods can block copper absorption. This can lead to copper deficiency, which causes anemia or even nerve damage. So, someone on chronic zinc might not need to avoid copper but should talk with a doctor before starting copper gluconate on top of it. It’s a two-way street: high copper can compete with zinc, too.

Penicillamine, a medication used for rheumatoid arthritis and Wilson's disease, binds to metals like copper to remove them from the body. Taking copper gluconate with penicillamine pretty much cancels out the drug’s effectiveness. Instructions often suggest spacing out doses by at least two hours, but people often miss this step, since copper supplements are marketed as harmless.

Hormone therapy and birth control pills show another link. Estrogen increases something called ceruloplasmin, a copper-carrying protein in blood. Higher copper levels pop up in people using these drugs, which might not cause issues for most. But for people with liver problems or certain metabolic conditions, it matters.

Antacids and acid blockers (like omeprazole or ranitidine) can affect copper absorption because they lower stomach acid, making it harder to break down minerals for absorption. In practice, copper deficiency from antacids rarely grabs headlines, but random cases show up in the medical literature. People with poor nutrition, or those on antacids long-term, face a bigger risk. So, if someone uses heartburn medication daily, adding copper gluconate without checking blood levels might cause trouble down the road. Symptoms like fatigue or tingling can sneak up slowly.

Many people believe dietary supplements don’t interact with medicines, but every month, pharmacists and doctors see examples proving the opposite. Older adults, people on chronic meds (especially antibiotics, diuretics, or chemotherapy), and those with stomach surgery often face the most risk. Copper isn’t as likely as iron to cause a drug disaster, but it can tip the balance for someone already juggling complicated regimens.

Annual bloodwork can help spot problems before they get worse. Sticking with a single multivitamin, instead of mixing separate supplements, keeps dosing in check. It also helps to bring a full list of every vitamin and drug, even occasional cold remedies, to every check-up. Explaining why a product is in the routine often sparks helpful advice from health professionals, catching small issues early. Open communication with a healthcare provider, backed by accurate information, makes all the difference between mild benefit and a risk that nobody saw coming.