Calcium gluconate has a story going back over a century, tracing roots to early efforts to treat calcium deficiencies and manage muscle-related conditions. Folks in the late 1800s saw hypocalcemia cause real trouble in both hospital wards and industrial workplaces, and research turned a lot of energy to forms of calcium that could be safely delivered by mouth and, if things became dire, by intravenous injection. The recognition that calcium chloride caused irritation and, in some cases, necrosis around injection sites pushed researchers toward gentler alternatives. Alfred Einhorn, the German chemist known for synthesizing procaine, singled out gluconic acid as a promising organic acid for complexing calcium in 1929, leading to calcium gluconate’s debut as a milder, more soluble salt. Within a generation, physicians made it a staple—especially for treating hypocalcemic tetany and arrhythmias—and manufacturers saw increased demand for food fortification by the end of the 1950s.

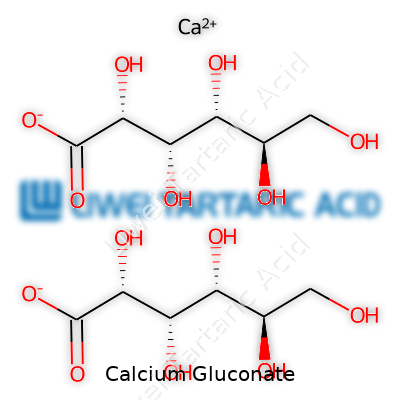

Calcium gluconate is a white, crystalline or granular compound that carries the formula C₁₂H₂₂CaO₁₄ for the monohydrate, though you’ll see C₆H₁₁CaO₇ on most drug labels. The name rings bells in both medical and food circles, and people have called it by other handles: Gluconic acid calcium salt, Cal-Glu, and even E578 in the European food additive system. Pharmaceutical companies pack it for both oral and intravenous use, while food makers fold it into juices, dairy alternatives, and baking mixes to shore up nutritional claims. In the industrial lab, it pops up in everything from electrolytic baths to concrete hardeners.

A jar of calcium gluconate offers a white or nearly white powder that dissolves slowly in cold water and wants no part of ethanol or ether. Its solubility in water rises with temperature, peaking at nearly 3% in near-boiling water, but even at room temperature, that’s enough for tablet and liquid formulation. Purity from reliable suppliers stays above 99%. What’s striking: the compound keeps its physical integrity well under normal storage and rarely causes caking or deliquescence if warehouse operators steer clear of excessive moisture. The taste lands a bit chalky with minimal bitterness—handy for makers of health drinks, less so for those after perfect flavor.

Pharmacopoeia standards, such as USP and EP, keep a tight rein on allowable impurities, water content, pH, and heavy metal traces. Most vials come stamped with batch numbers, expiration dates, and the all-important percentage of elemental calcium—just over 9%. Labels on pharmaceutical stock must show sterility for injectable forms and highlight contraindications where patient renal function is compromised or when digitalis toxicity looms. Food-grade material goes through additional screening under GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) status, and reputable brands display country-of-origin and traceability data alongside kosher or halal certifications if applicable.

Production lines for calcium gluconate kick off with gluconic acid, itself a product of glucose fermentation by fungi or bacteria, often Aspergillus niger or certain Penicillium strains. Calcium carbonate or calcium hydroxide then reacts with a solution of gluconic acid under controlled heat and stirring. This neutralization step churns out calcium gluconate in solution, and cooling allows the desired salt to crystallize out. The crystals go through filtration, washing, and drying, with the option of further recrystallization to dial up purity past food or pharmaceutical specs. The straightforward chemistry makes small-lot or pilot-scale preparation accessible, which helps with research and custom formulation.

In basic chemistry classes, students see calcium gluconate resist most simple decomposition under mild conditions—heat drives off water to yield the anhydrous form, but at higher temperatures, it can decarboxylate to simpler calcium carboxylates or carbonate. The chelation with gluconic acid gives it an edge over other calcium salts in minimizing precipitation with phosphate or oxalate ions in biological systems. In research labs, chemists look for ways to tweak the molecule for controlled-release applications or improved solubility, such as complexing it with polymers or switching to its magnesium analog for multi-mineral blends. These minor modifications may improve bioavailability for people with impaired calcium absorption or for those using tube feeding.

Doctors rely on calcium gluconate to treat hypocalcemia, bring tetany under control, reverse magnesium sulfate toxicity in eclampsia, and combat hyperkalemia’s dangerous effects on the heart. Emergency responders keep injection kits on hand to counteract burns from hydrofluoric acid—the only practical treatment available for fast-moving, deep tissue damage from that dangerous chemical. In the food world, folks add it to plant-based milk, juices, and cereals to reach the calcium levels found in dairy, creating real competition for traditional sources. Bakers use it as a dough strengthener, and cheese-makers sometimes turn to it for curd structure. Laboratory workers find it handy in culture media, and engineers try it out as a hardener in specialty concrete to improve curing rates.

Safe handling means dry gloves and goggles in the powder room, and sterile technique for the injectable product. Oral doses pose minimal risk for most adults, but large overdoses can cause constipation or kidney stones, particularly in those with a history of calcium imbalance. Rapid IV administration proves risky—arrhythmias or tissue necrosis threaten patients if guidelines are not followed. Industry regulators require electronic batch records, environmental monitoring, and detailed recall plans to keep pace with ongoing safety improvements. Quality-assurance teams constantly audit for heavy metals and microbial contamination, and new regulatory rules often demand more transparent supply chain mapping to catch adulteration or mislabeling before the product even reaches the shelves.

Innovation around calcium gluconate attracts both pharmaceutical scientists and food technologists looking for novel use cases. Researchers test its performance as a calcium source in slow-release supplements, try out nano-encapsulation for better absorption, and explore how added trace elements might support at-risk populations like the elderly or those with gut disorders. Food chemists look for ways to combine it with prebiotics to help stave off osteoporosis. Early successes in combining calcium gluconate with vitamin D or K2 hint at the potential for high-performing multinutritional tablets. Hospitals study combinations with amino acids to smooth out parenteral nutrition blends. The focus remains on solutions that raise absorption rates while keeping side effects at bay.

Toxicology studies consistently put calcium gluconate among the safer options in mineral therapy, though like any supplement or drug, there are exceptions. Tests in rodents and large mammals show high LD50 thresholds, and adverse reactions in people usually trace to intravenous misuse or underlying kidney impairment. Chronic misuse causes hypercalcemia, a risk made clear by early 20th-century cases before routine blood monitoring. Published literature documents rare cases of hypersensitivity or arrhythmia, pushing health agencies to amend their guidance. Safety assessments for food use consider daily intake alongside cumulative exposures from fortified waters and foods, leading nutritionists to adjust official intake recommendations for at-risk groups.

Future developments look promising for calcium gluconate, both as a standalone therapy and as part of enriched foods. Diet shifts and a push for better supplementation in aging populations are driving new delivery systems, such as chewables, dissolvables, or microencapsulated blends. Tech companies work on digital traceability to back up origin claims, spurred by increasing regulatory pressure. Pharmaceutical teams keep an eye on injectable forms for rapid burn treatment and high-risk cardiac interventions, with ongoing trials for improved shelf-stable preparations. Researchers hunt for greener production methods, aiming to swap chemical for biotechnological steps in the wake of growing demand for sustainable manufacturing. All these efforts spring from real-world needs—better mobility for the elderly, more effective emergency care, and growing confidence in the safety of daily nutrition.

Calcium gluconate sits among those medicines you hope to never need, but you’re glad it’s there when you do. In the emergency department, doctors often reach for it in urgent situations. It’s lifesaving for people exposed to hydrofluoric acid. That chemical, even in small amounts, causes severe burns and seeps through the skin, attacking nerves, blood vessels, and bones. Calcium gluconate—either as a gel applied to the skin or injected—pulls fluoride away from tissues, limiting damage and easing pain within minutes.

Doctors call on calcium gluconate when blood calcium levels drop too low, a problem called hypocalcemia. Muscles might cramp, nerves tingle, or, in serious cases, the heart stumbles out of rhythm. In hospital settings, especially after thyroid surgeries or in chronic kidney disease, intravenous calcium gluconate turns things around quickly. I’ve seen patients, anxious and shaky from low calcium, settle down just minutes after starting an IV.

Certain heart problems demand calcium on board fast. For someone with high blood levels of potassium—the kind of spike that sometimes knocks the heart out of sync—calcium gluconate’s job is to stabilize heart cells. It acts as a shield, buying crucial time until other treatments can start pulling excess potassium out of the body. Not every medicine gives such immediate reassurance to a doctor in a crisis.

People who take high doses of magnesium, whether for preeclampsia in pregnancy or other medical issues, may drift into muscle weakness or heart block if magnesium piles up. Here, calcium gluconate acts as an antidote—all the more important since hospital patients sometimes tip the balance between helpful treatment and dangerous side effects.

Calcium gluconate finds a place outside the emergency room, too. Tablets or oral solutions allow doctors to top up calcium for those who can’t get enough from their diet, or who lose calcium due to medications or illness. Taking care of bone health isn’t flashy, but it keeps bones strong and nerves firing just right. Even so, supplements don’t replace a good diet—cheese, greens, milk, or fortified foods deliver more than tablets alone.

Not every bottle of calcium gluconate provides benefit for everyone. Giving too much risks kidney stones or heart troubles. Doctors monitoring heart rhythms and kidney function make sure the solution does more good than harm. Major medical guidelines recommend careful dosing, especially for those with heart or kidney problems. In my experience, patients do best when healthcare teams check levels regularly, pace infusions gently, and pair treatment with advice about diet and medication side effects.

Too many still miss out on prompt treatment because they don’t know what’s available. Teaching healthcare workers about quick-response medicines improves outcomes. Clearer instructions on first aid for chemical burns, and public outreach, make a difference in both workplaces and the home. Companies handling strong chemicals keep calcium gluconate on site for a reason. A little preparation saves limbs and lives, not just workplace lawsuits.

Not every medical emergency demands the same approach. Calcium gluconate gets pulled off the shelf for some pretty urgent problems—low calcium levels, magnesium toxicity, and sometimes life-threatening hyperkalemia. Administering this medicine calls for care, know-how, and clear thinking. One wrong move and side effects can spiral, landing someone in worse shape than before.

Tablets or solutions can help refill calcium stores when someone’s just low or struggles to keep levels up over time. It doesn’t fix a crisis. Swallowing a pill takes time; not every gut absorbs the mineral equally. This route works for those who eat, keep food down, and don’t face a ticking clock. Chronic hypocalcemia ties closely to this method, such as in people with mild parathyroid problems.

Jump to a hospital setting, and the rules change fast. IV administration jumps straight into the bloodstream and starts working almost immediately. Doctors order IV calcium gluconate for real trouble—think muscle spasms that won’t stop, heart rhythm issues, or after a caustic hydrofluoric acid burn. Nurses set up an infusion, often diluting the medicine in saline or dextrose to soften any harsh sting to veins.

IV push gets reserved for true emergencies, and the dose creeps in slowly. Too fast, and patients might feel a hot flush, tingling, or their blood pressure could plummet. Once had to keep a close eye on a patient after an accidental rapid infusion—flushed face, sweating, and a dangerously irregular heartbeat. It served as a reminder: rushing saves no lives when the heart’s in the balance.

The spot for the IV needle makes a difference. Large, healthy veins (sometimes central lines) cut down on irritation and tissue death if there’s a leak. Smaller arm veins work if the dose gets diluted and goes in slowly. Blockage or collapse in these veins brings on extravasation, so staff must watch closely. I’ve learned that frequent line checks mean fewer calls to wound care.

Giving calcium gluconate isn’t as simple as opening a box. Improper use can stiffen muscles, mess up the heart’s rhythm, or cause burning pain around the needle. I’ve heard of tissue injury and long-lasting scars when a vein gets missed. Too much calcium mixed with certain drugs (like digoxin) throws off the whole plan and might stop the heart.

Smart policies and constant training help teams stay ahead of mistakes. Double-checking orders, using the right dilution, and flushing lines before and after keep people out of trouble. Most problems I’ve seen came from shortcuts—skipping steps or not checking compatibility. Role-modeling care, especially for a new nurse or doctor, protects everyone.

Good administration means more than following a protocol; it asks for presence and confidence. No step gets skipped: ask about allergies, monitor for signs of toxicity, keep emergency equipment close. If in doubt, reach for support or a second opinion. Patients notice when caregivers focus, and small actions—like explaining what the medicine may feel like—can ease a lot of fear.

Calcium gluconate often shows up in emergency kits, especially where hospitals treat patients with low calcium levels or those facing heart trouble linked to low calcium. I've seen it used in severe magnesium overdoses too, particularly in critical care settings. It acts fast, and that can save a life. But just like many medications, things can go sideways if someone doesn't look out for the risks.

Whenever someone receives calcium gluconate, some common reactions pop up pretty often. Flushing or a warm feeling can come on quickly, especially if the dose goes in too fast. That sensation of warmth and tingling—usually around the face and neck—can feel unsettling, but usually calms down when the doctor slows down the injection.

Stomach troubles also get reported. Nausea, vomiting, or mild cramps sometimes hit after the infusion, especially when taken by mouth. This isn't unique to calcium gluconate; high amounts of calcium in general tend to sideline the gut in the same way. In clinics where I worked, nurses always recommend drinking water and monitoring for these symptoms, which keeps things from getting worse.

Some risks with calcium gluconate deserve serious attention. If the solution leaks outside the vein, that patch of skin can get damaged, turning red or irritated, and could even lead to tissue injury. This happens more often with fast or careless infusions, so careful monitoring makes all the difference. Once in a while, patients can develop a slow or irregular heartbeat, especially if someone already has heart disease or other electrolyte problems. I've met people whose heart tracing changed during the IV, needing a quick intervention from the cardiac team.

Too much calcium in the blood might build up if someone already struggles with kidney problems. Elevated calcium levels might cause confusion, muscle weakness, or even kidney stones. In my practice, regular blood checks and kidney monitoring always played a part in keeping patients safe. These steps help spot trouble before symptoms spiral out of control.

Though genuine allergic reactions don't happen very often, hives, trouble breathing, or swelling need an immediate response. Just about every medical setting keeps resuscitation gear nearby for this reason. Any sign of allergy means stopping the infusion and getting help right away. Most nurses in my circle always review allergy histories thoroughly before any new medication goes in, and calcium gluconate is no exception.

Clear communication between healthcare workers and patients protects against unnecessary side effects. Anyone getting calcium gluconate should speak up about any burning or unusual feelings right away. Hospitals can lower risks by checking calcium levels before and after giving it, watching the IV site closely, and avoiding rapid administration. In outpatient clinics, patients need guidance on hydration and the early signs of side effects so problems get flagged before they worsen.

Simple steps—like verifying kidney function, tailoring the dose, and making sure equipment is in place for emergencies—help prevent bigger complications. Real-world skills, teamwork, and practical safeguards reduce chances for harm, making sure this helpful medicine works in the safest way possible.

Calcium gluconate finds its spot in hospitals and medicines cabinets everywhere. Doctors give it to bring calcium levels up when a person runs low, work to calm muscle cramps from low calcium, or rush to use it during heart emergencies and toxic drug exposures. On paper, it looks pretty safe. My old clinical preceptor used to say, “Your grandmother’s bones would thank you, but check her pill box first.” He meant it literally—mixing the wrong medicines could get risky.

One thing about calcium: it likes to stick together—with food, with other medicines, sometimes even clogging up its own benefit. Take tetracycline, a common antibiotic. If someone pops a calcium tablet too close to their antibiotic dose, that calcium will grab those tiny drug molecules and lock them up in the gut. Instead of fighting infection, the medicine just slips out the body, unused. This same snag happens with other antibiotics—doxycycline, ciprofloxacin, and levofloxacin. Doctors and nurses often remind people to space these drugs apart by at least two hours. This isn’t fine print; missing the warning can mean a pointless round of antibiotics.

Digoxin is another medicine that needs careful attention. Many older adults rely on it for cushioning fast or irregular heartbeats. Adding calcium gluconate can whip a heart into dangerous rhythms, especially if potassium is already low. ER staff check these levels before giving calcium through an IV. This isn’t hypothetical—the FDA and many journals have published warnings about cases called “stone heart” or sudden arrhythmias that landed patients in real trouble.

Those with kidney disease know this better than anyone. Kidneys usually do the heavy lifting—washing out extra calcium. With sluggish kidneys, the risk for too much calcium climbs quickly. The extra calcium settles in blood vessels and tissues, doing harm to hearts, brains, and kidneys. My neighbor’s dad went to dialysis three times a week, and his doctor had him steer clear of calcium supplements unless blood work proved a need.

Cancer patients needing extra calcium face their own risks. Certain chemotherapy treatments already raise calcium. Adding more, unless closely supervised, can tip things into dangerous territory and create kidney stones or mental confusion. People with conditions like sarcoidosis or too much parathyroid hormone also stack up calcium too quickly, even without pills. Healthcare teams usually run regular lab checks for these folks.

Simple routines can save hours of frustration. Pharmacists tell patients to list every medicine and supplement, not just prescription drugs. Electronic health records help, but they only work if the user shares all over-the-counter and herbal products. Hospitals double-check lab results before starting calcium therapy. Out in the community, doctors teach people to look for signs like belly pain, muscle twitching, or confusion, and to bring in the pill bottles themselves to visits.

The upside: calcium gluconate helps many people live better. Staying ahead of interactions starts with honest conversations and careful attention, not just a label on a bottle.

Calcium Gluconate tends to pop up in conversations when doctors look for quick ways to bump up calcium levels in the blood. Patients hear about it in emergency rooms and from pharmacists. As someone who’s watched a loved one go through low calcium after surgery, I know confusion often circles around the numbers. Sometimes it’s about vials, sometimes it’s tablets, and the numbers on the bottles don’t always match what the doctor says.

Doctors don’t pick a one-size-fits-all dose of Calcium Gluconate. They look at what’s going on in your body. Low blood calcium after surgery? Intravenous treatment comes into play. Mild deficiencies sometimes get tablets. Severe symptoms—muscle cramps, tingling, even heart trouble—mean more urgent action. From the rough-and-ready world of clinical practice, a common starting point for acute low calcium in adults equals 10 milliliters of a 10% Calcium Gluconate solution, which packs 90 milligrams of elemental calcium per dose. That means only a small chunk of each milliliter holds actual calcium your body can use.

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and peer-reviewed journals offer direct advice. For severe drops in calcium, a doctor may give 1–2 grams through a vein slowly—never fast. The heart reacts badly to sudden swings in blood chemistry. Tablets for ongoing low calcium often range from 0.5 to 2 grams, taken two to four times each day. Kids get much smaller doses based on their weight and age, and disease history always matters.

No over-the-counter buzz compares to professional advice with Calcium Gluconate. Getting a dose wrong can put someone in the hospital or even risk their life. Too much pushes calcium way up, and nobody wants kidney stones, confusion, or skipped heartbeats. Too little leaves the basics unchecked—bone health, nerve impulses, muscle control. Guidance from the US National Institutes of Health warns everyday supplements should rarely reach more than 1,000–1,200 milligrams of elemental calcium a day for adults from all sources, unless prescribed more. That’s not just tablets or vials—it includes food, too.

Noticing side effects isn’t something to brush off. Patients who feel strange—from tingling lips to fast heartbeats—need to talk to the team managing their care. The doctor takes recent blood tests and kidney health into account before making the call. I’ve noticed plenty of people trust internet suggestions, but the internet can't see your lab results. Trusted sources like clinical guidelines, the FDA, and major health system pharmacists all say high-dose injections only belong under supervision—never at home or for mild issues.

Clearer labels and better conversations between patients, pharmacists, and prescribers can help. Regularly updating clinical guidelines so nurses and doctors work from the same playbook cuts down errors. Family members benefit from double-checking numbers with professionals, especially when handling complicated health problems. Getting the right amount of Calcium Gluconate isn’t just about the numbers—it’s about making sure those numbers fit the person.